|

I always pass on good advice. It's the only thing to

do with it.

It is never any use to one's self.

- Oscar Wilde,

An Ideal

Husband (1895), Act I

|

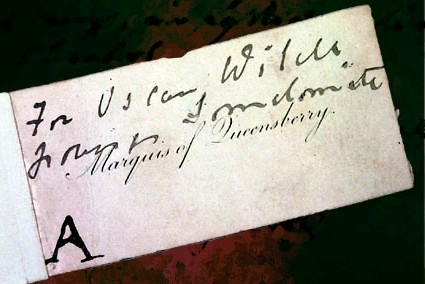

Four days later, on 18 February 1895, Queensberry called

at the Albermarle Club, of which both Wilde and his wife were

members. He left with the hall porter a card on which

he had written "to Oscar Wilde posing as a sodomite" - although,

in fact, the last word was mis-spelt as "somdomite". Partly

because of the mis-spelling, Queensberry's conduct has been

widely portrayed, in books and movies of Wilde's life, as the

frenzied actions of a man whose fury and malevolence had him

teetering on the brink of raving lunacy. In fact, it was

nothing of the sort; it was very much worse; it was a carefully

constructed trap of extraordinary cleverness.

To induce Wilde to prosecute him for libel - which was undoubtedly

Queensberry's intention - he had to defame Wilde publically

and in writing. As Mr. Justice Wills remarked (perhaps

a little naively) at the last of the subsequent trials:

Lord Queensberry

has drawn from these letters [Wilde's letters to Lord Alfred

Douglas] the conclusions that most fathers would draw, although

he seems to have taken a course of action in his method of interfering,

which I think no gentleman would have taken, whatever motives

he had, in leaving at the defendant's club a card containing

a most offensive expression. This was a message which

left the defendant no alternative but to prosecute, or else

be branded publically as a man who could not deny a foul charge.

Had Queensberry baited his trap in any other way, there was

a chance that a prosecution would not eventuate. Had the

same words been sent in a private letter to a third party, there

is the possibility that the third party would not have informed

Wilde of the correspondence; and, even if it came to Wilde's

attention, a private communication might have been ignored without

exposing Wilde as one who had "no alternative but to prosecute,

or else be branded publically as a man who could not deny a

foul charge". In later correspondence with his son, Queensberry

referred to the card as "the booby trap" - a perfectly accurate

expression, in every sense.

Yet at the same time, Queensberry was careful to formulate

that foul charge in language which he hoped to be able to

justify, without undertaking the onerous burden of proving that

Wilde had actually committed unnatural vices. The use

of the word posing made it very much easier for Queensberry

to advance a plea of justification, yet took none of the sting

out of the defamation. As Sir Edward Clarke QC contended

in opening the libel case to the jury:

The words

of the libel are not directly an accusation of the gravest of

all offences - the suggestion is that there was no guilt of

the actual offence, but that in some way or other the person

of whom those words were written did appear - nay, desired to

appear - and pose to be a person guilty of or inclined to the

commission of the gravest of all offences.

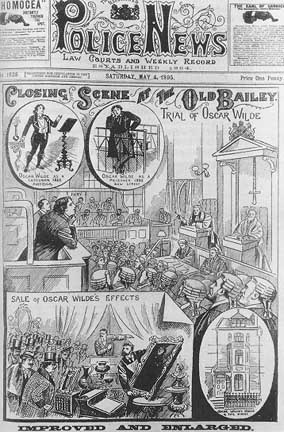

The trap was baited, and Wilde took the bait. Wilde

prosecuted Queensberry for criminal defamation. At the

conclusion of Wilde's evidence, and even before Edward Carson

QC (subsequently Sir Edward, and later Lord Carson) had completed

his opening speech for the defence, the prosecution was withdrawn.

Wilde, as prosecutor, submitted to a verdict of Not Guilty

in favour of Queensberry, expressly on the basis that it was

true in substance and in fact that he had posed as a sodomite,

and that this statement was published in such a manner as to

be for the public benefit. That very afternoon, Wilde

was arrested; at his first trial in late April, the jury were

unable to agree on a verdict; but at his second trial, in May,

he was found guilty on eight counts of committing acts of gross

indecency with another male person and given the severest

sentence that the law allows, namely imprisonment with hard

labour for two years.

These three trials together constitute an extraordinary chapter

in England's literary, social and legal history. But to

the modern lawyer, they are chiefly of interest for three reasons:

first, as exemplifying the perils faced by a prosecutor or plaintiff

in defamation proceedings; secondly, as containing one of the

most celebrated cross-examinations in the history of advocacy;

and thirdly, as raising very serious concerns regarding the

severity with which Wilde was prosecuted.

|

In this world there are only

two tragedies.

One is not getting what one wants,

and the other is getting it.

- Oscar Wilde,

Lady Windermereís

Fan (1892), Act III

|

|