|

... the real tragedies of life

occur in such an inartistic manner that they hurt

us by their crude violence, their absolute incoherence,

their absurd want of meaning, their entire lack

of style.

- Oscar Wilde,

The Picture

of Dorian Gray (1890), Ch. 8

|

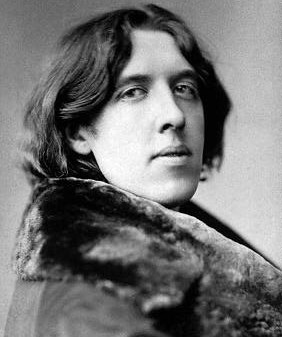

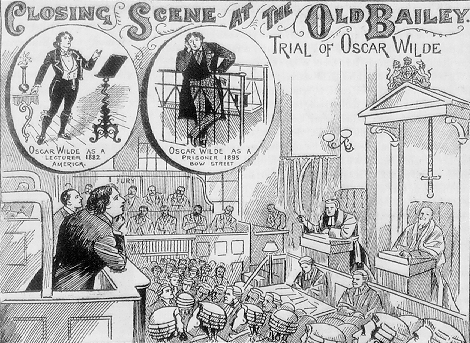

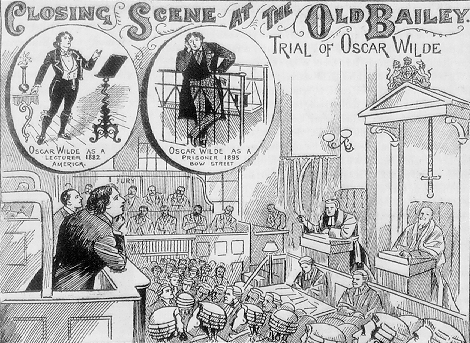

In the months of April and May, 1895, England's foremost

playwright - Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde - featured

in three successive trials in consecutive sessions of the Central

Criminal Courts. Just weeks earlier, his greatest dramatic

creation, The Importance of Being Earnest, had experienced a

tumultuously successful opening in the West End. But the

dramas which were to unfold, just a few blocks away at the Old

Bailey, amounted to a theatrical tragedy which even the greatest

playwright would not have dared to invent.

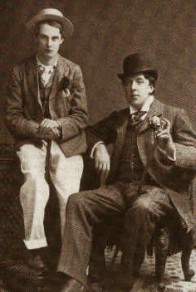

Wilde and "Bosie" Douglas

|

Really, if the lower orders don't set us a good example,

what on earth is the use of them

?

- Oscar Wilde,

The Importance

of Being Earnest (1895), Act I

|

Wilde's problems arose out of his association with Lord Alfred

("Bosie") Douglas, a younger son of the Marquess of Queensberry.

In his Autobiography, published in 1929, Bosie confessed

that there occurred between him and Wilde "familiarities" of

the kind "which not infrequently take place among boys at English

public schools"; but that, "of the sin which takes its name

from one of the cities of the Plain there never was the slightest

question". They both shared an interest in young men of

a lower social order - in the argot of today's gay community,

"rough trade" - and co-operated with one another in seeking

out opportunities to gratify that particular interest.

|

|

|

| Oscar

Wilde and Lord Alfred ("Bosie") Douglas

|

The first sign of trouble came in 1893, when certain letters

written by Wilde to Douglas fell into the hands of Alfred Wood,

an unemployed clerk whose income appears to have derived from

prostituting himself through a male brothel conducted by Alfred

Taylor, and by some small-time blackmail. Wood claimed

that he had found the letters in the pockets of an old suit

of clothes given to him by Bosie Douglas. This implausible

story only begs the question as to the nature of the relationship

between Wood and Douglas, by which the former obtained access

to the latter's rooms and clothing. In a letter which

Wilde wrote to Douglas from prison, subsequently published as

De Profundis, Wilde referred to an earlier attempt by Wood to

blackmail Douglas on account of some improprieties which occurred

between Douglas and Wood at Oxford. Both Wilde's and Wood's

evidence confirmed that it was Douglas who introduced them to

one another.

Wood, with confederates named Allen and Clibborn - apparently

more experienced blackmailers - attempted to extort payment

from Wilde for the return of the letters, but (if Wilde's version

is to be believed) were only modestly successful. In evidence,

Wilde included this account of his interview with the blackmailer

Allen:

I said,

'I suppose you have come about my beautiful letter to Lord Alfred

Douglas. If you had not been so foolish as to send a copy

of it to Mr. Beerbohm Tree, I would gladly have paid you a very

large sum of money for the letter, as I consider it to be a

work of art.' He said, 'A very curious construction can

be put on that letter'. I said in reply, 'Art is rarely

intelligible to the criminal classes.' He said, 'A man

offered me £60 for it'. I said to him, 'If you take my

advice you will go to that man and sell my letter to him for

£60. I myself have never received so large a sum for any

prose work of that length; but I am glad to find that there

is some one in England who considers a letter of mine worth

£60.' He was somewhat taken aback by my manner, perhaps,

and said, 'The man is out of town'. I replied, 'He is

sure to come back'. And I advised him to get the £60.

He then changed his manner a little, saying that he had

not a single penny, and that he had been on many occasions trying

to find me. I said that I could not guarantee his cab

expenses, but that I would gladly give him half-a-sovereign.

He took the money and went away.

After Allen's unsuccessful attempt to extort a substantial

payment, Clibborn made a further foray at Wilde's house. As

Wilde described the encounter in his evidence:

I went out

to him and said, 'I cannot bother any more about this matter'.

He produced the letter out of his pocket, saying, 'Allen

has asked me to give it back to you'. I did not take it

immediately, but asked: 'Why does Allen give me back this letter?'

He said, 'Well, he says that you were kind to him, and

that there is no use trying to "rent" you as you only laugh

at us'. [The word "rent", in this context, was a contemporary

slang term for blackmail.] I took the letter and said,

'I will accept it back, and you can thank Allen from me for

all the anxiety he has shown about it'. I looked at the

letter, and saw that it was extremely soiled. I said to

him, 'I think it is quite unpardonable that better care was

not taken of this original manuscript of mine'. He said

he was very sorry, but it had been in so many hands. I

gave him half-a-sovereign, and then said, 'I am afraid you are

leading a wonderfully wicked life'. He said, 'There is

good and bad in every one of us'. I told him he was a

born philosopher, and then he left.

In fact, the blackmail cost Wilde rather more than two half-sovereigns:

he made a further payment to Wood - £20, by his own account,

or £35, according to Wood's version - in either event, a sizeable

sum of money at a time when 10 shillings (one-half of a pound)

represented a working man's weekly wage. In evidence,

both Wilde and Wood maintained that this payment was not a result

of blackmail, but merely an act of kindness to assist Wood to

start a new life in America - no doubt a convenient fiction,

as it was in neither party's interests to admit the true character

of the payment.

Although the blackmail attempt did not cost Wilde very dearly

in financial terms, it had the result that scandal started to

spread. Wood's confederates produced copies of the apparently

compromising letters, and circulated them amongst Wilde's theatrical

and literary colleagues - including one copy which went to the

actor-manager, Beerbohm Tree, who was then producing A Women

of No Importance at the Haymarket Theatre. Another copy

apparently came to the attention of Bosie's father, the Marquess.

|

Little boys should be obscene

and not heard.

- Oscar Wilde,

(attributed)

I never play cricket. It

requires one to assume such indecent postures.

- Oscar Wilde,

(attributed)

|

|