|

The Trial of Australia's Last Bushrangers[1]

It is perhaps a slight anachronism that the first lecture in a series presented by the Queensland Museum under the general title of "Queensland 1901" deals with events which did not occur until the following year. Yet the murder trial of Patrick and James Kenniff, in the Supreme Court of Queensland in November 1902, is historically significant and interesting from a number of viewpoints.

It was amongst the first major trials to be conducted under the Queensland Criminal Code, an enactment which came into effect on the first day of the Twentieth Century - the same day as Federation - 1 January 1901. It would indeed be difficult to over-state the significance of this legislative initiative: although the idea of collecting and codifying the entire body of criminal law in a single Act of Parliament had been under discussion in England for over a Century, Queensland became the first place in the British Empire to do so. The Criminal Code was almost entirely the work of Queensland's Chief Justice, Sir Samuel Griffith.

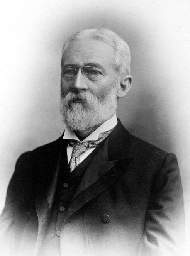

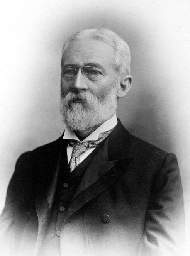

Sir Samuel Griffith

and the Criminal Code

Sir Samuel is remembered in this State, and in this Country, for many things: as the pre-eminent barrister of his era; as a politician and, at times, a somewhat controversial one; as Premier (or, as the position was then sometimes called, "Prime Minister") of the Colony of Queensland on two occasions; as one of the recognised leaders of the Federation movement in this Country; and as one of the nation's most respected jurists, Chief Justice of Queensland for 10 years (1893 to 1903), and Chief Justice of Australia for 16 years (1903 to 1919).

|

|

The Right Honourable Sir

Samuel Walker Griffith, PC, GCMG

Chief Justice of Queensland,

13

March 1893 to 5 October 1903

Chief Justice of Australia, 5 October 1903 to

17 October 1919

Trial Judge at the Kenniff Trial

Photograph

from The

National Library of Australia's Federation Gateway |

He is not, perhaps, quite so well remembered for his literary work: his English translation of the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri received unanimously unflattering reviews when it was published in 1912, the most generous being The Bulletin's patronising remark that "No harm can come from a perusal of Sir Samuel Griffith's attempt"[2], and a less tactful reviewer pronouncing that "Unfortunately the poetry of Dante has escaped almost entirely from Sir Samuel's industrious fingers"[3]. It is reported that when Griffith presented a copy to the leader of the Sydney Bar, Sir Julian Salomons QC, the latter asked Griffith to autograph the fly leaf, explaining that "I should not like anyone to think that I had borrowed the book, even less should I like anyone to think that I had bought it"[4]. Another wag has contrasted Griffith's poetical efforts with the recreation of England's greatest Equity Judge, Lord Eldon, whose amusement it was to "translate" well known ballads into the language of legal instruments - the suggestion being that Sir Samuel's translation of the Divine Comedy unwittingly achieved a similar outcome[5].

In spite of - rather than due to - his literary efforts, Sir Samuel has the rare distinction of a major University named in his honour - a distinction which he shares with only one other Australian lawyer (Sir Alfred Deakin), two sailors (James Cook and Matthew Flinders), two colonial governors (Lachlan Macquarie and Charles La Trobe), a soldier (General Sir John Monash), a professor of English (Sir Walter Murdoch), and two politicians (John Curtin and Edith Cowan).

It is, however, Griffith's work as a statutory draftsman that continues to have the most enduring and pervasive influence after more than 100 years. His legislative output was extraordinarily varied and, taken as a whole, truly prodigious.

I will take this opportunity, if I may, to express my vehement disagreement with the central thesis of a recently published book[6], which contends that the draft of the Australian Constitution adopted in Sydney at the first National Australasian Convention of 1891 was not principally the work of Sir Samuel Griffith, but in truth a draft prepared by the Tasmanian Attorney-General, Andrew Inglis Clark, with Griffith's involvement being (so it is suggested) limited to turning "Clark's draft into a strong, tightly worded and well-structured first draft of the Australian Constitution which would survive". This is not the occasion for a comprehensive refutation of Professor Botsman's conspiracy theory, so I will confine myself (on this occasion) to making just six points:

(1) Professor Botsman's thesis seeks to convey the impression that, in 1891, Griffith was something of a "Johnny-come-lately" to the Federation movement, whereas Inglis Clark had been working on his draft for some time prior to the 1891 Convention, with the advantage of a year's travel to England and the United States where he drew upon what he perceived to be the most positive aspects of both countries' systems of government. In fact, Griffith's active involvement in the Federation movement pre-dates by some years any formal participation by Inglis Clark. As early as 1883, the Queensland Executive Council resolved to invite the Imperial Government in London to "move in the direction of a federal union"[7]. This led to the Sydney Intercolonial Conference of that year (attended by representatives of the six Australian colonies, as well as New Zealand and Fiji), at which Griffith represented Queensland as Premier, and successfully moved a resolution for the establishment of a "Federal Australasian Council"[8], and drafted the legislation to give effect to this proposal[9].

(2) The notion that Griffith was in any way reliant on Inglis Clark to bring to his attention either the strengths or the weaknesses of the US system of government is hardly supported by Griffith's own assessment, by which he "ranked neither [Inglis] Clark nor [Alfred] Deakin as his superior in knowledge of the United States of America", whilst generously acknowledging that his fellow Queensland delegate and erstwhile political opponent, John Murtagh Macrossan, was "the best informed of us all on the subjects on which knowledge was useful, and especially with regard to the American Constitution"[10]. Griffith's perception of his own role at the 1891 Sydney Convention, he expressed in the words "my work ... was very hard, for it fell to my lot to draw the Constitution, after presiding for several days on a Committee, and endeavouring to ascertain the general consensus of opinion"[11].

(3) Others who played a major role in the Federation movement, and especially at the 1891 Convention, credited Griffith with primary responsibility for the drafting. In the course of debate at the Convention, Sir Henry Parkes - President of the Convention - remarked, "this bill, [for] the preparation of which ... Griffith deserves so much praise, will be a document remembered as long as Australia and the English language endure"[12]. Sir Alfred Deakin agreed, remarking that "as [a] whole and in every clause the measure bore the stamp of Sir Samuel Griffith's patient and untiring handwork, his terse, clear style and force of expression. ... few even in the mother country or the United States ... could have accomplished ... such a piece of draftsmanship with the same finish in the same time."[13]

(4) The extent of Griffith's role in preparing the 1891 draft has been thoroughly documented and examined by legal and academic authors of the highest repute, none of which lend the slightest credence to Professor Botsman's contention. The starting-point is surely the massive and highly regarded work of Dr John Quick and Sir Robert Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, published in 1901. The authors - one of whom was himself a key player in the Federation movement - unequivocally pronounce (in respect of the 1891 draft) that "Sir Samuel Griffith, who had been appointed Chairman of the Constitutional Committee, ... had the chief hand in the actual drafting of the Bill"[14]. The same view is resoundingly supported in what may fairly be regarded as the leading work on the subject by a professional historian, The Making of the Australian Constitution by Professor J.A. La Nauze[15], who concludes that "the final form of the Constitution contains not only much of Griffith's text of 1891, but his lofty corrections of the words of the later and lesser draftsmen of 1897".

(5) There is no mystery - let alone, as Professor Botsman would seem to want it, a conspiracy of silence - regarding the fact that Inglis Clark did produce a draft constitution prior to the 1891 Convention. Inglis Clark's draft was fully reproduced in Australia's leading legal journal as long ago as 1958[16]. Whilst there are (of course) similarities between Inglis Clark's draft and the draft adopted by the 1891 Convention, they are two very different documents, both in form and in substance. Speaking as one who, through professional practice, has become intimately familiar with Griffith's style of legislative drafting, there is no doubt in my mind that the elegance and simplicity of the 1891 draft flowed almost entirely from Sir Samuel's pen. Just as one (of many) examples, one may compare clauses 5 and 6 of Inglis Clark's draft with clause 1 in Chapter II of Griffith's draft[17]. Inglis Clark took 84 words, comprised in two clauses, to vest executive power in the Queen, and to provide for the exercise of that power by the Governor-General. The style is awkward and prolix, containing phrases such as "The executive power and authority of and in the Federal Dominion of Australasia is hereby declared to continue and be vested ... [etc.]", and "It shall be lawful for the Queen from time to time to appoint a Governor-General to exercise in the Federal Dominion of Australasia during Her Majesty's pleasure, and subject to the provisions of this Act, such executive powers, authorities, and functions as Her Majesty may deem necessary or expedient to assign to him". Griffith managed to convey the same meaning, in a mere 26 words, with much greater clarity:

"The Executive power and authority of the Commonwealth is to be vested in The Queen, and shall be exercised by the Governor-General as the Queen's Representative."

(6) Perhaps most compellingly, when Inglis Clark (as Attorney-General) presented to the Tasmanian House of Assembly the bill produced by the Second Convention of 1897-98, he reminisced about his role in the drafting of the 1891 bill and - according to a contemporary report in the Hobart Mercury[18] - "claimed part of the responsibility, or glory, or whatever they might call it". This is hardly consistent with the image which Professor Botsman seeks to convey, of a modest man who chose to remain out of the public spotlight, even to the point of allowing Griffith to take the credit for what was really Inglis Clark's own work. Rather, it seems that Inglis Clark was content to accept the credit, where it was due, for his subordinate role as a member of Griffith's drafting committee[19].

But I digress. Whatever debate there may be concerning the extent of Sir Samuel Griffith's role in drafting the Australian Constitution, there is no doubt that the Queensland Criminal Code was almost entirely his own work. Even today, as we celebrate the centenary of this monument to Griffith's legal skills and industriousness, the criminal law of Queensland remains almost entirely in the form in which he drafted it. There have, of course, been some changes. The death penalty, and punishment by flogging, have been mercifully obliterated. New offences, to cope with modern technical innovations, have been introduced: for example, hijacking of aircraft and unlawful use of motor vehicles. As society's views have changed regarding the relative seriousness of different offences, some penalties have been increased and other reduced, whilst some conduct - notably homosexual offences, and also pretending to practice witchcraft - have been decriminalised. There have been cosmetic changes, including the adoption of "gender neutral" terminology. But, for the most part, Griffith's words survive.

One of Sir Samuel's most celebrated successors as Chief Justice of Australia, Sir Owen Dixon, described his great predecessor as having a "legal mind of the Austinian age" which was "dominant and decisive". According to Dixon, Griffith "did not hesitate, he just felt that he knew; and that what he knew was right"[20]. Although this view of Sir Samuel may be readily confirmed by reading the judgments which he produced during his 26 year career on the bench, it is nowhere better illustrated than in his drafting of the Criminal Code. Where a lesser draftsman might use several synonyms or near-synonymous words for fear that the omission of any one of them might leave a loophole, Sir Samuel's practice was confidently to choose the single most appropriate word; he was definitely not of the legal school which created such platitudinous tortologies as "give, devise and bequeath" or "mortgage, charge and hypothecate".

The almost impenetrable complexity of many enactments - including many modern enactments, and especially those concerned with revenue matters - can often be put down to one or other of two causes. On one hand, the drafter may state a general principle, but state it too broadly, so it then has to be cut down with various exceptions, exclusions and qualifications. Or, on the other hand, the drafter does not state a general principle at all, so that the enactment becomes a catalogue of rules applicable to specific instances. Griffith's "Austinian" mind worked differently. Having determined a general principle, he expressed it in such clear and precise language that there was no need, either to restrict the general principle with specific exceptions, or to enhance it by reference to specific instances where the general principle applies.

Take, for example, section 24 of the Criminal Code, dealing with mistakes of fact, which remains unamended (save for the most minor cosmetic changes) since it emerged from Griffith's pen in the late years of the 19th Century. It provides:

"A person who does or omits to do an act under an honest and reasonable, but mistaken, belief in the existence of any state of things is not criminally responsible for the act or omission to any greater extent than if the real state of things had been such as he believed to exist."

Those responsible for drafting the new Federal Criminal Code have somehow contrived to express the same principle in more than four times as many words (236, as compared with Griffith's 54), divided into two sections, four sub-sections, and six sub-sub-sections - all of which is accompanied by a note drawing attention to yet another section (comprising a further three sub-sections and a further four sub-sub-sections) - providing for specific circumstances where the general principle does not apply[21].

It is a tribute to Griffith's drafting that it was adopted, virtually without change, both in Western Australia and in Papua New Guinea. Also in the British African colonies of Lagos, the Sudan and Nigeria, Griffith's draft was adopted with few changes. Tasmania and the Northern Territory have since adopted criminal codes which, although not so reliant on Griffith's draft, were strongly influenced by it.

Sir Samuel Griffith was not merely the draftsman of the legislation under which Patrick and James Kenniff were brought to trial; he was also the trial judge. And, as we will see, the case (particularly against James Kenniff) raised an important question of principle, involving the interpretation of the Criminal Code. In the context of the current Centenary of Federation celebrations, it is also worth recalling that, less than 12 months after presiding at the Kenniff trial, Griffith was appointed to be the first head of Australia's new High Court.

From an historical perspective, the Kenniff trial is interesting, not only for the dry and dusty legal history which accompanies it, but also for the fact that the Kenniffs are frequently referred to (not entirely inaccurately) as "Australia's last bushrangers". One author goes so far as to label Patrick Kenniff as "Queensland's Ned Kelly"[22]. The Macquarie Dictionary defines a "bushranger" as being "a bandit or criminal who hid in the bush and led a predatory life"; a definition which the Kenniffs undoubtedly satisfy. I do not doubt that it may be possible to identify more recent instances of bandits and criminals who hid out in the bush, and who led predatory lives, but in this respect I feel that the Macquarie definition is rather too wide. To my mind at least, the concept of a bushranger involves the likes of Dan Morgan, Ben Hall, Bold Jack Donohue, Captain Thunderbolt, Captain Moonlight, and (of course) the Kelly Gang - outlaws distinguished by their skill as horsemen, their ability to survive in the bush, their use of carbine firearms, and their ruthlessness as robbers and (in many instances) murderers. The Kenniffs surely fit this mould.

Did the Kenniffs get a fair trial?

The issue which interests me - as a professional lawyer, and merely an amateur historian - is whether the Kenniffs got a fair trial. In the result, I have little doubt that Patrick Kenniff did commit the murder for which he was convicted and hanged, and that James Kenniff's involvement in the same murder was at least sufficient to justify the 16 year prison term which he served. Yet if one believes the principle that justice should not only be done, but be seen to be done, I suggest that one may entertain very serious reservations as to the fairness with which justice was administered against them.

I should, at this point, disclose a personal interest. It happens that my great-grandfather owned a store at Yuleba[23] which was robbed by the Kenniff Gang in 1898 or 1899. Patrick Kenniff's conviction and gaol sentence over this armed robbery has a particular significance in the present context, which I will come to shortly.

It is also worth mentioning - if it is not already apparent - that I am a great admirer of Sir Samuel Griffith's. Both my admiration for Griffith, and my family connection with a robbery committed by the Kenniffs, naturally led to my interest in the Kenniff story. But I hope it will be apparent that neither consideration has influenced by judgement, either as a professional lawyer or as an amateur historian, in revisiting the circumstances of the Kenniff trial.

Background of the Kenniff Brothers[24]

Brothers Patrick and James (Jimmy) Kenniff came to Queensland in the early 1890s. They grew up in New South Wales, where both had brushes with the law from a young age - mainly for stealing horses and cattle.

When the Kenniffs first came to Queensland, it was to start a new life as honest stockmen and horsebreakers. But they did not keep out of trouble for long. In March 1895, Pat Kenniff was sentenced to a 4 year gaol term for horse-stealing, whilst Jimmy received a 3 year sentence. They served their time in the prison at St Helena Island in Moreton Bay, and both were described as "model prisoners".

|

|

|

|

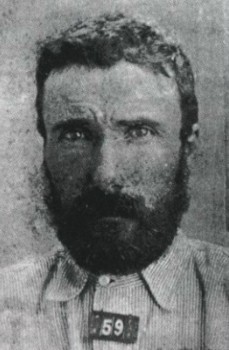

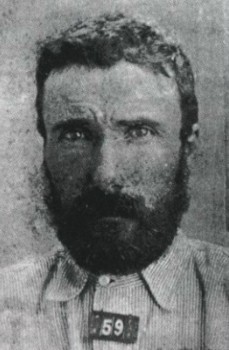

Patrick

(left) and James (right) Kenniff

Photographs

from Queensland

Heritage, vol.2 no.1, November 1969 |

By 1897, the Kenniffs were out of gaol and, with their father, took up a large grazing lease known as Ralph. However, suspicions were aroused that the Kenniffs had gone back to their bad old ways, when the manager of a neighbouring property called Carnarvon calculated that over 1,000 head of cattle had gone missing.

Because the owners of Carnarvon did not trust their neighbours, they decided to buy Ralph at an inflated price, and then evicted the Kenniffs. At the following muster, a fight broke out between the manager of Carnarvon (Albert Dahlke) and Jimmy Kenniff, when Dahlke became upset by the huge number of cattle on Ralph which had apparently been stolen from Carnarvon and other neighbouring properties.

After their eviction from Ralph, the Kenniffs took to a nomadic existence and were often seen riding armed. The Commissioner of Police became so concerned that a new police station, the Upper Warrego Police Station, was established on the very spot where the Kenniffs' hut and stockyards had earlier stood on Ralph.

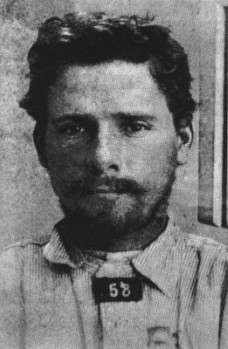

In early December 1897, the Kenniffs stole 40 horses in the Carnarvon region, and set off towards Toowoomba. They kept to the high country and back tracks, and made for Yuelba to load the horses on a train.

The Kenniffs came up with a clever diversion to lure the local police away from Yuelba. They held up a general store, stealing some of the merchandise, as well as cash and cheques from the safe. They then created a false trail, leading out of town. Whilst the police were off following the false trail, the Kenniffs circled back into town, and loaded the stolen horses on the train for Toowoomba.

|

|

|

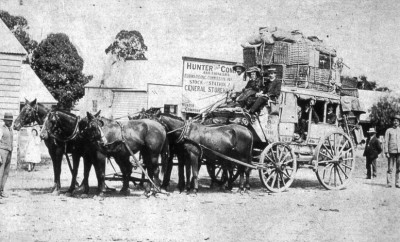

The Cobb & Co. coach

outside Hunter & Company's

Store in Yuelba

as it would have looked at

the time of the Kenniff Gang's hold-up.

The

last Cobb & Co. coach ran between Yuelba

and Surat in 1924.

|

The train left Yuelba at 9 am, and arrived in Toowoomba after dark. As the Kenniffs had planned, there were no stock inspectors at the Toowoomba railway station at that late hour. So they were able to sell the horses and, after a short spending spree in Toowoomba, return to their home-country. Their plan had worked perfectly - or so it seemed.

But they made one mistake. Patrick Kenniff cashed a cheque, stolen from the store in Yuelba, at a pub in Toowoomba. The publican and two other witnesses remembered his doing so.

During 1898 and 1899, the Kenniffs were actively stealing horses and other livestock over an area ranging from the Carnarvons, west to Augathella. Eventually both Pat and Jimmy were captured. Each benefited from the sympathy of local juries - Jimmy in Charleville, and Pat in Roma - who had little respect for wealthy land-owners, and perhaps a grudging admiration for the Kenniffs' courage and daring. But it was a different matter when it came to holding up a general store.

On 22 August 1899, Patrick Kenniff was convicted by a Roma jury in connection with the theft of the cheque from Hunter's Store in Yuelba. He received a 3 year sentence but, with remissions, was released on 12 November 1901.

On 21 March 1902, police at Roma took out a warrant against Patrick and James Kenniff for stealing a pony on or about 25 October 1901. The warrant was wired to the Upper Warrego Police Station, with instructions to find and arrest Patrick and James Kenniff.

A police posse set out, consisting of the officer in charge, Constable Doyle, along with the manager of Carnarvon, Albert Dahlke, and an Aboriginal tracker, Sam Johnson.

On the morning of Easter Sunday, 1902, the three men arrived at Lethbridge's Pocket, a known Kenniff campsite. Sam Johnson was riding in the lead, and spotted the Kenniffs riding towards him. The Kenniffs fled, and were chased by the police contingent.

Doyle and Dahlke caught Jimmy Kenniff, and dismounted him. Patrick Kenniff had apparently escaped. Sam Johnson was sent to retrieve the party's packhorse, which had been left behind at the start of the chase. When Sam Johnson returned with the packhorse, neither Constable Doyle nor Albert Dahlke was to be seen. Patrick and Jimmy Kenniff galloped towards Sam Johnson, who fled to find help.

|

|

|

|

The

Victims:

Constable

George Doyle (left) and Albert Dahlke

(right), manager of Carnarvon Station

Photographs

from Mostly

Murder

by Hugh McMaster, 1999 |

A later expedition found evidence of a gun-fight, with bullet marks in the surrounding trees. There were the remains of three small fires, under which clotted blood was found; a large rock bearing stains similar to burnt blood; and fragments of broken bones. When Constable Doyle's horse was found, its pack-bags contained about 200 pounds of charcoal later identified as burnt human remains, including some personal belongings of Doyle and Dahlke.

It became a major priority of the Commissioner of Police and the Government to track

down the Kenniff Brothers, and bring them to justice. A reward of £1,000 - a huge sum of money in those days - was offered for information leading to their arrest.

A massive man-hunt was organised, involving over 50 police, 15 of them trackers. The chase took three months.

The final arrest was not, however, the "show-down" which many had expected. The pair were surprised at a camp near the Maranoa River, just south of the town of Mitchell, and gave up without a fight.

|

|

|

Scene of the Kenniff arrest

Near the Maranoa River just south of Mitchell,

as

depicted in a contemporary newspaper report.

Note the police officers removing their boots

in an unsuccessful attempt to sneak up on

the Kenniffs.

sketch

from Sunday

Truth

newspaper, 6 July 1902

|

The Kenniffs were transported to Rockhampton, where they were committed for trial in the Supreme Court at Brisbane for the wilful murder of Constable George Doyle and Albert Dahlke. The case was set down before Queensland's senior Judge, Chief Justice Sir Samuel Griffith.

The only surviving witness to the events at Lethbridge's Pocket was the Aboriginal tracker, Sam Johnson. His evidence was one of the most significant and controversial features of the case. As he was not a Christian, his evidence was not given on oath. The defence lawyer tried to discredit him, urging the jurors that they should not convict on what he called the "evidence of one blackfellow".

At one stage during the trial, the defence solicitor cross-examined Sam Johnson as to the time when the gun-fight occurred. He asked, "What time of day was it when the bullets were flying about - sun go up, go down, or him on other side?" To this, Sam Johnson answered, "About 8 o'clock". His dignified answer to such an insulting question produced much laughter in the public gallery of the courtroom, but also reinforced his credibility as an honest and reliable witness.

Unlike many men of his era, Chief Justice Griffith had no sympathy with any form of racial discrimination. Many years earlier, as Premier of Queensland, Griffith had strongly opposed the importation of "Kanaka" labourers - South Sea Islander people who were brought to Queensland to work in the cane fields in conditions of virtual slavery. When it came his turn to sum up to the Jury, Chief Justice Griffith firmly rejected the defence argument that the Jury should not convict on the evidence of one "blackfellow". He told the Jury, in no uncertain terms, that they were to treat the evidence given by Sam Johnson in the same way that they would treat the evidence of the any other witness.

|

|

"Tracker" Sam

Johnson.

The sole surviving witness to the events

at Lethbridge's Pocket, whose evidence helped

to convict the Kenniffs, despite the defence

lawyer urging the Jury not to convict on the

"evidence

of one blackfellow".

photograph

from Mostly

Murder

by Hugh McMaster, 1999

|

After Sir Samuel Griffith's summing-up in "clear, cold tones of measured directness", the Jury took only one hour to return with a verdict of "guilty". Sir Samuel said that he "entirely agreed" with the verdict. The law only allowed one possible sentence to be passed on persons convicted of wilful murder. Contemporary reports say that it was in a "shaken" voice that Chief Justice Griffith condemned both Patrick and James Kenniff to death by hanging.

The law did not allow any appeal from the Jury's verdict, but the new Criminal Code provided that the trial judge could reserve any questions of law which arose out of the case for consideration by the Full Court. At the request of the defence lawyer, the Chief Justice reserved two questions for consideration by the Full Court - whether there was sufficient evidence of death, and whether there was sufficient evidence to convict both Patrick and James Kenniff. These questions were considered by a Full Court consisting of the trial judge, Sir Samuel Griffith, and Justices Cooper, Chubb and Real.

All members of the Court agreed that there was sufficient evidence of death, and sufficient evidence to support the Jury's verdict against Patrick Kenniff. By majority, three of the four judges upheld the conviction of James Kenniff. But the fourth judge, Justice Real, did not accept that James Kenniff's guilt had been proved beyond any reasonable doubt.

In Justice Real's view, the evidence showed that James Kenniff was in the custody of Constable Doyle when Doyle was last seen alive. His Honour argued that the shooting of Doyle and Dahlke may have occurred as Patrick Kenniff attempted to free his brother, without Jimmy being in any way involved. This produced a heated exchange between Justice Real and Chief Justice Griffith.

Although the majority of the Court upheld the conviction of James Kenniff, the Government considered that Justice Real had raised sufficient doubts about James Kenniff's criminal responsibility that he should not be put to death. Patrick Kenniff was hanged in Boggo Road Gaol on 12 January 1903. Jimmy's sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he served 16 years in gaol. After his release, Jimmy returned to Central Queensland and worked as a stockman, and later as a miner. He died in 1940.

The summary set out above does not purport to be a comprehensive analysis of the facts. Where conflicting accounts have been published, I have generally preferred Sir Samuel Griffith's version, based (as it was) on the sworn testimony of eye-witnesses. In the Full Court, lawyers for the Kenniff Brothers did not challenge the accuracy or fairness of Griffith's summary of the evidence[25]. In any event, this summary suffices as a backdrop to the concerns which I would express regarding the fairness of the Kenniff trial.

Trial by a "Jury of their Peers"

There is a common misconception in our community that the Great Charter of 1215, commonly known by its Latin title of Magna Carta - significantly enhanced the rights of ordinary citizens. Largely, Magna Carta was not concerned with the rights of ordinary citizens, or subjects; it was concerned with the rights of the barons who procured King John to sign it at Runnymede near Windsor on 15 June 1215. Where Magna Carta does confer rights on ordinary citizens, it is more a by-product of the barons' concern to shore up their own rights.

One of the barons' concerns was that they should not be subjected to trial by juries of their social inferiors. So, the 39th clause of Magna Carta pronounces that[26]:

"No man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land."

So a trial by a "jury of one's peers" became part of the law of England, guaranteeing to the ordinary subject - as much as to the barons whom it was intended to protect - the right to a trial by citizens of equal social standing. This principle became so well entrenched as to be reflected in the US Bill of Rights, guaranteeing to "the accused ... a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed"[27]. So also the Australian Constitution guarantees the right to a jury trial in respect of serious Federal offences[28]; and it is interesting to note that this provision was adopted, almost verbatim, from Sir Samuel Griffith's draft of 1891[29], and a similar provision is to be found (although in very different words) in Inglis Clark's draft which preceded the 1891 Convention[30]. Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, published between 1765 and 1770, and still widely regarded as the greatest work on English law, states:

"The right of trial by the jury, or the country, is a trial by the peers of every Englishman, and is the grand bulwark of his liberties, and is secured to him by the Great Charter."

It is strange, then, to find that Patrick and James Kenniff were not tried by a "jury of their peers", but by a select or "special" jury, composed exclusively of men from an entirely different walk of life - professional men, accountants, merchants, brokers and the like - better educated and more affluent men, who would have little sympathy with men like the Kenniffs. How did this come about?

For some 35 years prior to the Kenniff trial, there had been on the statute-books of Queensland an enactment empowering the Crown to apply for a "special jury", but that power had "hardly ever been availed of"[31]. The Act did not specify the circumstances in which such an application may succeed, but previous such applications had only been granted in exceptional circumstances: for example, the trial of bank directors charged with issuing false balance sheets, which required the jury to examine complex sets of accounts[32], or a case in which there had previously been an abortive trial before an ordinary jury[33].

What made the Crown's application on this occasion even more disturbing is that the judge who heard and granted the application - Mr. Justice Virgil Power, then the Central Judge resident in Rockhampton - proceeded on the basis that the Crown did not need to produce evidence showing there were special circumstances to warrant the application, and his Honour seems to have thought that the Crown's application should be "granted as a matter of right"[34]. Regrettably, the Court was not informed of a case in 1891, where Mr. Justice Chubb refused the Crown's application for a "special jury"[35]. The notion that such an application should be granted to the Crown "as a matter of right" was plainly erroneous, and was not followed on the occasion when the next such application was made to the Supreme Court some 20 years later[36].

The circumstances relied on by the Crown Solicitor as justifying the order for a "special jury" comprised four elements, namely:

"1. The complicated nature of the evidence for the prosecution.

2. The large number of important exhibits.

3. The technical nature of the evidence of medical experts to be called for the prosecution.

4. The mass of circumstantial evidence to be considered."

At that stage of proceedings, the Kenniffs had the benefit of representation by a young but extremely able counsel, T.J. Ryan, subsequently a Queen's Counsel and Premier of Queensland. But Ryan's hands were tied. He was not permitted to challenge the assertions contained in the Crown Solicitor's affidavit, nor to be informed of details of the Crown's case beyond the general propositions that the evidence would be complicated, that the exhibits would be numerous and important, that the evidence of medical experts would be technical, and that there would be a mass of circumstantial evidence. It is clear, even from the sanitised version contained in the law reports, that the hearing of the application became a veritable "slanging match" between bench and bar. Justice Power was not prepared to brook any attempt to impugn the Crown Solicitor's good faith, describing him as "a high official having knowledge of the matter", whose "power is not likely to be abused"[37].

|

|

T[homas] J[oseph] Ryan

In Rockhampton, the Kenniffs were represented

by an able - though inexperienced - counsel. T.J.

Ryan subsequently became a Queen's Counsel and Premier

of Queensland (1915 to 1919)

photograph

from Griffith

University's Queensland Studies Centre

|

What is apparent, with the benefit of hindsight, is that the application for a "special jury" was quite obviously a tactical manoeuvre by the prosecuting authorities, to avoid the possibility of a sympathetic jury. Counsel for the prisoners should have been permitted to challenge the Crown's bare assertion that the complexity of the case necessitated a "special jury", and Justice Power ought to have exercised his own judgement on that question rather than deferring to the opinion of the "high official" responsible for conducting the prosecution.

Perhaps a more experienced counsel than Ryan could have out-manoeuvred the prosecution. For example, the so-called "technical ... evidence of medical experts" went merely to identifying the remains found at Lethbridge's Pocket as being burnt human remains: an astute defence lawyer could have formally admitted as much, thereby excluding the need for any medical evidence, without conceding that the remains were of Doyle and Dahlke, let alone that the Kenniffs were responsible for their deaths. Given the clearly erroneous approach taken by Justice Power, the Kenniffs might have been well advised to appeal, or to seek reservation of the point for determination by the Full Court. Neither course was adopted, with the result that the application granted by Justice Power determined the course of subsequent proceedings before Chief Justice Griffith.

It is open to debate whether there was any substantive miscarriage of justice, insofar as the Kenniffs were denied the chance of a sympathetic jury; perhaps, in the result, what occurred served (rather than prejudiced) the interests of justice, if it was merely to avoid having a sympathetic jury, rather than to secure an antipathetic one. Even so, the fact that the Kenniffs were deprived of their right to a "jury of their peers" - and that they were deprived of this right by a proceeding (before Justice Power) which was plainly erroneous in law - leaves a bitter taste in one's mouth.

The blame does not lie solely at the feet of Justice Power, nor at the feet of the able but inexperienced counsel (T.J. Ryan) representing the Kenniffs. A significant portion of the blame must be carried by the prosecuting authorities who, under our legal system, ought never to engage in tactical manoeuvres to deny an accused person of every benefit and advantage which the law allows. It has long been our law - and had long been our law, even in 1902 - that prosecuting authorities are "ministers of justice": it is their duty to place the material evidence fully and fairly before the appropriate court, and not to "struggle for a conviction"[38].

One has the unhappy feeling that, as against the Kenniffs, the prosecuting authorities viewed their functions as being more consistent with the role of an American-style "District Attorney". The entire pretext for the Crown's application to empanel a "special jury" disappeared when, at the commencement of his summing-up, Sir Samuel Griffith began by informing the "special jurors" that "The facts of the case [are] very simple"[39].

Competence of Defence Representation

In the proceedings before Justice Power in Rockhampton, the Kenniffs had (as already mentioned) the benefit of very able, if inexperienced, counsel. In the Full Court, too, their representation was at a high level of competence. Yet at their trial, where perhaps it mattered most, no counsel appeared for them; they were represented by a solicitor, of no great prominence, against two of the State's leading barristers who appeared for the prosecution.

It is exceedingly easy, with the benefit of a century's hindsight, to criticise the approach taken by an advocate of limited experience in an unusually difficult case. Even so, the Kenniffs' solicitor made some very fundamental errors.

He launched a scathing attack on Sam Johnson's reputation, asking him in cross-examination whether he had the nicknames of "Deadwood Dick" or "Joe the Liar", and asking him whether it was the case that people frequently said he was a man who could not be relied upon. Not surprisingly, Johnson denied these assertions. Yet, when evidence was called on behalf of the Kenniffs, no witness could be produced to support these allegations against Johnson. The only thing which the solicitor achieved by attacking Johnson's reputation was to expose his own clients to cross-examination regarding their character and reputations - a very risky course indeed, given the character and reputations of Patrick and James Kenniff - as it is (and was in 1902[40]) a well-settled rule that an accused person may not be cross-examined as to matters of character or reputation except in very limited circumstances, including where the defence has squarely raised issues concerning the character or reputation of a material prosecution witness.

To cross-examine Sam Johnson in pidgin English was an extraordinary blunder. At the very least, one might have expected any competent advocate - indeed any person of intelligence - to have judged, from Sam Johnson's evidence in chief (if not from his evidence at the committal proceedings) that Johnson was reasonably fluent in ordinary English, and that any attempt to belittle or denigrate Johnson by cross-examining him in pidgin had the propensity to back-fire in exactly the way that it did.

Another major tactical error was the calling of hopelessly implausible alibi evidence. The fault may not be entirely that of the defence lawyer, as he was bound by his instructions; but, at the very least, the Kenniffs should have been warned of the risks which this course entailed. Unless their alibi testimony was believed - an outcome which could not seriously have been expected, given the weakness of that testimony and the weight of evidence against it - its effect was always going to be highly prejudicial: people do not ordinarily manufacture false alibi evidence except to conceal their own guilt, and the jury were perfectly entitled to draw the rational inference that, by giving false evidence and allowing false evidence to be given on their behalf, the Kenniffs were acting out of a consciousness of their own guilt.

So far as one can glean from contemporary newspaper reports, the solicitor representing the Kenniffs simply failed to advance any intelligible or coherent case - let alone any plausible case - for the defence. Apart from the worthless alibi evidence called on behalf of the Kenniffs, their solicitor seems to have focussed his argument on the proposition that the jury could not be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that Doyle and Dahlke were dead. Yet this appears to have been the strongest aspect of the prosecution case. There was no doubt that Doyle and Dahlke had entered Lethbridge's Pocket in search of the Kenniffs, armed with a warrant for their arrest. It is true that nobody - not even Sam Johnson - saw their lifeless bodies. But they were not seen alive again. Even ignoring Sam Johnson's testimony, the physical evidence showed that there had been a gun-fight in Lethbridge's Pocket, that blood had been spilt, and that burnt human remains were left in the vicinity and in the pack-bags of Doyle's horse. Included with the remains were personal items which were clearly identified as having belonged to Doyle and Dahlke. On this evidence, no other conclusion was open but that Doyle and Dahlke had met their deaths at Lethbridge's Pocket. If there was any room for doubt, it could only be a doubt as to whether both Patrick and James Kenniff were responsible for their deaths.

Faced with such evidence, there was little that any advocate could have done to save Patrick Kenniff from the gallows. But the same cannot be said in respect of James Kenniff. As Justice Real's powerful dissenting judgment demonstrates, a logical hypothesis was open on the evidence, consistent with James Kenniff's innocence[41].

As the representative of both brothers, the Kenniffs' solicitor was in a difficult position. Whilst both brothers continued to maintain their innocence, and to corroborate one another's specious claim that they were nowhere near Lethbridge's Pocket at the relevant time, their solicitor was bound by those instructions. Yet it would seem safe to assume that, despite their other defects of character, the Kenniffs had a strong family loyalty. One may speculate as to whether the trial might have taken a very different course if an experienced advocate had clearly explained to Patrick Kenniff that, whilst he had no chance of saving himself, there was a chance of saving his brother.

The approach taken in the defence case really amounted to an "all or nothing" proposition: if the Kenniffs' alibi story was believed, they were both innocent; if that story was disbelieved, they were both guilty. This approach left very little scope for the jury even to consider the possibility that, whilst Patrick's guilt had been proved beyond any reasonable doubt, there remained more than reasonable scope to doubt that James Kenniff participated in the death of Doyle or Dahlke. Even if no evidence had been given by or called on behalf of the Kenniffs, the jury needed to be satisfied that James Kenniff's role was something more than that of a passive onlooker to the murders. And, had the defence case been presented in that way, it is difficult to see how a jury could not have entertained reasonable doubts regarding the extent of James Kenniff's involvement, given that the prosecution evidence showed him to have been unhorsed and unarmed, in Doyle's custody, when Doyle and Dahlke were last seen alive. Although inconclusive, rudimentary forensic examination conducted at the scene suggested that shots had been fired by a man mounted on horse-back, and there was nothing to suggest any shots fired by a man standing on the ground. Whilst it was no doubt possible to hypothesise a series of events in which James Kenniff actively participated in the deaths of either or both victims, nobody could safely say that such an hypothesis was the only one open on the evidence; and if the evidence permitted an alternative hypothesis, under which Doyle and Dahlke met their deaths without any active involvement on the part of James Kenniff, his guilt was not proved beyond any reasonable doubt.

Acting in Concert

On any view, James Kenniff - being dismounted, unarmed, and in Constable Doyle's custody - could not have instigated the course of events which led to the deaths of Doyle and Dahlke; the only reasonable hypothesis is that Patrick Kenniff did so. In these circumstances, the case against James Kenniff involved the application of sections 7 and 8 of the Criminal Code which, as Justice Cooper noted in the Full Court, are effectively declaratory of the rules which previously applied under the Common Law[42]. Under these provisions, a person is criminally liable for the commission of an offence, not only if the person actually does the act or makes the admission which constitutes the offence, but also if the person aids, abets, counsels or procures the commission of the offence, or if the offence is committed in the course of prosecuting a common unlawful purpose.

In summing up to the jury, Chief Justice Griffith appears to have put the case on the basis that the deaths of Doyle and Dahlke occurred whilst the brothers were prosecuting an unlawful purpose in conjunction with one another: according to a contemporary newspaper report[43], his Honour said:

"It was not likely that both prisoners fired at Doyle, though they might have. ... If there were acting in concert, both were guilty. If both formed the purpose before Dahlke was shot, and determined to resist apprehension and for that purpose fired at Doyle, they were guilty."

With the utmost respect to Sir Samuel Griffith, it is difficult to see how such a case can be constructed from the evidence. There was no suggestion that the Kenniffs were doing anything unlawful at Lethbridge's Pocket - or had formed a common intention to do anything unlawful - before the arrival of Doyle, Dahlke and Johnson. Doyle came to arrest them, holding a warrant for that purpose. Strangely, the warrant - against both Patrick and James - was based on the alleged theft of a pony on or about 25 October 1901. But on 25 October 1901, Patrick Kenniff was still in gaol, serving his sentence in connection with the robbery at Yuelba - he was not released until 12 November of that year.

The Kenniff Brothers fled to avoid arrest. Can it be said that this manifested any common unlawful purpose? In theory, a common unlawful purpose can be formed without any communication. But in this context, it is difficult to see how any opportunity arose for them to form a common intention, rather than each of them acting instinctively and independently to avoid being taken into custody.

James Kenniff was captured, dismounted and restrained. From that moment, it is plain that he was in no position to form any common intention with his brother. Possibly, they had agreed in advance that, if either was captured, the other would attempt to rescue him. But there was no evidence of any such pact, and it is at least equally probable that Patrick acted of his own volition in coming to his brother's rescue.

It seems not unlikely that, as Chief Justice Griffith postulated, Dahlke was shot first. If that is so, it occurred whilst James remained in Doyle's custody, and it is quite impossible that James could have participated in any way.

The actual circumstances of Doyle's death are a matter of conjecture. It is quite possible that James broke free from Doyle's custody whilst Doyle was still alive, or that Doyle released James from his custody so as to defend himself. But even if James was free from Doyle's custody for a brief period before Doyle's death, there was no evidence to suggest that James had access to a firearm, or otherwise had the means to assist Patrick in killing Doyle, let alone evidence that he actually did so. No doubt James was anxious to escape from Doyle's custody, and no doubt Patrick acted with the intention of producing that result. But section 8 of the Criminal Code is not satisfied merely because two people, independently of each other, form an intention to achieve a similar outcome; there must be a common intention, formed by them, to prosecute an unlawful purpose in conjunction with one another.

In the Full Court, each member of the majority - Justice Cooper[44], Justice Chubb[45], and Chief Justice Griffith[46] - considered that the existence of a joint common purpose could be inferred from the fact that, following the deaths of Dahlke and Doyle, both brothers charged at Sam Johnson. As Justice Chubb put it[47]:

"In my opinion complicity may be established by subsequent equivocal acts or conduct from which a reasonable inference of guilt can be drawn. Was there any act or conduct of James Kenniff of an equivocal character which cast upon him the burden of satisfying the jury that the act or conduct was, quâ the murder innocent? I think there was, viz.: The act of the prisoners immediately after the murder in galloping together in pursuit of Johnson. From this I think the jury could have reasonably drawn inferences that the prisoners were under the belief that Johnson was an eye witness to the murder, and in concert they pursued him for the purpose of destroying testimony of the crime - he being, other than themselves, the only eye witness of it."

With the greatest respect, this reasoning is entirely tendentious. It assumes that James would only have joined with his brother in charging at Johnson if it were the case that James was criminally implicated in the deaths which had already occurred. Yet it cannot seriously be suggested that James would have conducted himself differently, had he been an innocent bystander to the murders committed by his brother - that, having been freed by his brother from police custody, and having witnessed his brother commit two murders, he would have stood by and said (in effect): "You're the one who killed Dahlke and Doyle. I didn't ask you to. I'm not going to help you escape apprehension and punishment for their murders."

At worst, James Kenniff's conduct established that he was an accessory after the fact to the murders committed by his brother[48]; it is not evidence capable of supporting an inference that he was criminally implicated in those murders. In the Full Court, Justice Cooper also seems to have thought that an adverse inference could be drawn from the attempt by both Kenniffs to manufacture a false alibi[49]. It is trite to say that, where an accused person is shown to have manufactured or utilised false evidence in the defence of a criminal charge, this may be relied upon as supporting an inference that the person is acting under a "consciousness of guilt". But in the present context, that simply begs the question as to what guilt James Kenniff may have been conscious of. It is hardly likely that an unsophisticated bushman would have understood the technical rules of law relating to accessory liability for the commission of a criminal offence, including the offence of murder. James Kenniff knew that he had escaped from police custody, knew that his brother had assisted him in escaping from police custody, knew that his brother had committed murders in assisting him to escape from police custody, and knew that he had (in turn) assisted his brother in escaping apprehension for those murders. The knowledge that his brother had committed murder was, in itself, more than sufficient reason for James Kenniff to acquiesce in the manufacturing and use of false evidence. If his conduct showed a "consciousness of guilt", there was more than sufficient guilt for him to be conscious of - including his brother's guilt of murder, and his own guilt as an accessory after the fact to the murders committed by his brother - without inferring that he was conscious of having committed conduct which had the legal effect of making him guilty of murder as a principal offender.

In 1902, the law did not allow for any appeal against a criminal conviction by a jury - it was not until 1913 that the Court of Criminal Appeal was created[50]. Until then, the only appellate review available in respect of criminal convictions was by way of the process adopted in the Kenniff case, under which questions of law could be reserved for the consideration of the Full Court. This process permitted the Full Court to review only questions of law - if, as a matter of law, the evidence was sufficient to support a guilty verdict, it was not the function of the Full Court to review the merits of the jury's verdict. Happily, in modern times, rights of appeal in criminal cases are much more extensive, and guilty verdicts are often set aside on the grounds that the verdict is "unsafe and unsatisfactory". I have little doubt that, in modern times, this is precisely the approach which any appellate court would take in respect of James Kenniff's murder conviction.

The Course of the Trial

Originally, the Kenniffs were arraigned on an indictment jointly charging them with the murders of both Dahlke and Doyle. Chief Justice Griffith held that this was improper, and that there must be a separate trial in respect of each alleged murder. His Honour required prosecuting counsel to elect on which of the charges he would proceed, and counsel elected to proceed in respect of the charge regarding the murder of Doyle.

What occurred was, to that extent, perfectly fair, reasonable and proper - save for this: that the prosecution was not required to make its election, and did not make its election, until the close of the prosecution case. The consequence is that, throughout the whole of the prosecution case, the defence solicitor did not know whether he was defending a charge in relation to the murder of Dahlke, a charge in relation to the murder of Doyle, or (possibly) both charges.

In all likelihood, the evidence on either charge would have been the same, or substantially the same. But there was some evidence which could have been regarded as relevant to a charge in respect of the murder of Dahlke, but irrelevant to a charge in respect of the murder of Doyle. For example, there was evidence of a conversation between the Kenniffs and the head stockman at Carnarvon, just two days before the alleged murders, when Patrick Kenniff, brandishing a revolver, uttered the words, "Whatever Dahlke gets, you will get the same". No doubt this evidence was admitted as being relevant to prove that Patrick Kenniff (and perhaps also James Kenniff, who participated in the same conversation) felt a degree of animosity towards Dahlke; the relevance of that conversation, in respect of the alleged murder of Doyle, is less readily apparent. Similar comments may be made in relation to evidence of an earlier altercation between James Kenniff and Dahlke, following a muster at Carnarvon.

It is fundamental to the fairness of a criminal trial that the accused should know precisely what charge or charges he is facing. The fact that the charges remained uncertain until the conclusion of the prosecution case may have significantly prejudiced the conduct of the defence. Evidence which might have been the subject of objection, as being irrelevant or otherwise inadmissible in respect of one charge, may have been erroneously placed before the jury as relevant to the charge which did not ultimately proceed. Moreover, in cross-examining prosecution witnesses, the Kenniffs' solicitor could not know whether to focus on issues pertaining to Doyle's death, or that of Dahlke.

It is obvious why, in the result, prosecuting counsel elected to proceed with the charge in respect of Doyle's death, rather than Dahlke's. Four reasons spring to mind. First, there had been a troubled history between Dahlke and the Kenniffs, and a sympathetic jury might have thought that in some ways Dahlke brought the Kenniffs' enmity upon himself. Secondly, whereas Doyle was acting in pursuance of his duty as a police officer in attempting to apprehend the Kenniffs, Dahlke was acting in an entirely voluntarily capacity, and a sympathetic jury might have thought that his involvement was tainted by a degree of officious vigilantism, if not a vendetta against the Kenniffs. Thirdly, because Doyle was acting in his capacity as a police officer, even a sympathetic jury might regard his murder as a particularly serious matter. Fourthly, and perhaps most fundamentally, the evidence tended to suggest that Dahlke was the first to die, whilst James Kenniff was still in Doyle's custody, making it somewhat more likely that James was actively involved in Doyle's death. One cannot criticise the prosecution for electing to proceed in respect of the stronger case. But that election should have been made at the outset, rather than at the conclusion of evidence for the prosecution.

Surprisingly, the defence solicitor did not complain about the unusual course taken at the trial, at least so far as appears from either the official law reports, or from contemporary newspaper reports. Nor is it an issue which the defence solicitor sought to have reserved, as a question of law, for the consideration of the Full Court.

It is impossible to say whether the evidence would have been any different if the trial had taken a more regular course - whether the defence solicitor would have objected to evidence which was not objected to, would have asked different questions in cross-examination, would have called different evidence in the defence case, or perhaps would not have called any evidence at all. All that can be said is that the proceedings were irregular, and that there was a possibility that the irregularity may have been harmful to the defence.

Full Court proceedings

There is also a most unsatisfactory feature of the proceedings in the Full Court, where the trial judge (Sir Samuel Griffith) sat as a member of the bench to review the proceedings conducted by him at first instance. This was not strictly irregular, because the proceedings in the Full Court did not technically constitute an appeal. So it was legally permissible for the trial judge to sit as a member of the appellate bench, to review his own decisions at first instance. However, if formal objection had been taken, there were strong grounds for objecting to the participation of the Chief Justice in the Full Court proceedings, on the basis that he had prejudged the very issues which the Full Court was to consider.

At the close of the prosecution case, the Kenniffs' solicitor made a submission that there was no case to go to the jury. In rejecting that submission, Chief Justice Griffith necessarily concluded that there was sufficient evidence to be left to the jury concerning Doyle's death, and sufficient evidence to be left to the jury of the guilt of both prisoners[51]. Those were the very questions which were reserved for consideration by the Full Court.

Moreover, following the jury's verdict, Sir Samuel Griffith expressed himself ("In a voice that betrayed some emotion"[52]) as entirely agreeing with the jury's verdict, and failing to see "how they could have given any other verdict".

It is, of course, settled law that a judge should not participate in any case where there is a reasonable apprehension that the judge has a predetermined view of the issues, or is otherwise unable to consider the issues without prejudice or partiality. Surely, the remarks made by Sir Samuel Griffith following the jury's verdict - if not his Honour's earlier ruling regarding the sufficiency of evidence - raised (at the very least) a reasonable apprehension that his Honour had already formed a concluded opinion on the matters reserved for the Full Court's consideration.

Counsel for the Kenniffs did not, however, object to Sir Samuel Griffith's participation in the Full Court proceedings. Had the Full Court been evenly divided, the result would have been particularly unsatisfactory, since Sir Samuel Griffith - as the presiding Judge - would have had the casting vote. It may be said, however, that his Honour's participation in the Full Court proceedings became irrelevant, since only one of the four judges would have quashed the conviction of James Kenniff.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Members

of the Full Court (from left):

Chief Justice

Sir Samuel Griffith, Mr Justice Sir Pope Cooper,

Mr Justice Patrick Real, Mr Justice Charles

Chubb

Photographs

from the Queensland Courts

Homepage |

Whilst there is force in this analysis, it ignores the powerful influence which the presiding Judge - and especially a Judge of Sir Samuel Griffith's eminence - carries with his judicial brethren. If either Justice Cooper or Justice Chubb felt any doubts regarding the correctness of the verdict against James Kenniff, the Chief Justice's participation in the Full Court proceedings may have assisted to remove those doubts. His participation was quite vocal, drawing attention to evidentiary matters supporting the jury's verdict, and engaging in heated exchanges with Justice Real.[53]

Certainly, according to modern legal standards, Chief Justice Griffith should not have participated in the Full Court proceedings in light of the views which he had earlier expressed regarding the merits of the case. Certainly, in accordance with modern authority, his participation in the proceedings of the Full Court would be regarded as having so infected the independence of the other members of the bench as to result in a miscarriage of the entire proceedings[54]. But the proceedings in the Full Court are not only objectionable by modern standards; they were objectionable by standards which were well-established even in 1902. Fifty years earlier, in a celebrated case[55], the Lord Chief Justice of England (Lord Campbell) said:

"I am glad, for the sake of a pure administration of justice, that the application has been made. The proceedings in question are much to be censured. [The Justice], as a rated inhabitant of the appellant parish, was clearly interested in the appeal. If he had done his duty, he would have withdrawn from the Court during the hearing of the appeal. ... He did not vote; nor was there any voting; but he remained in Court, as a member of it; and therefore his presence vitiated the proceedings."

Similarly, in the Kenniff case, "for the sake of a pure administration of justice", Sir Samuel Griffith ought not to have participated in the Full Court proceedings. And, despite the fact that a majority of the Court upheld the convictions of both Patrick and James Kenniff even after discounting the vote of Chief Justice Griffith, his very presence and participation contaminated the proceedings.

|

|

|

|

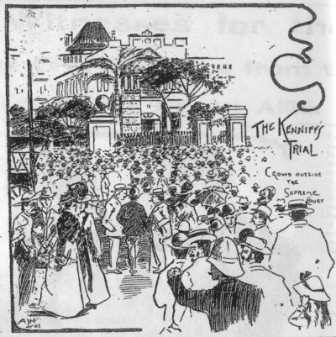

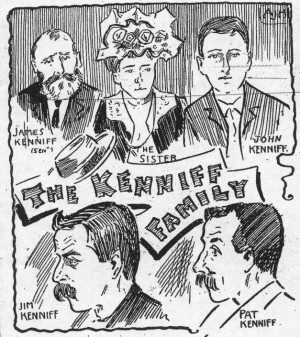

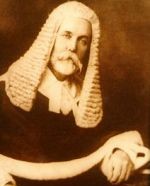

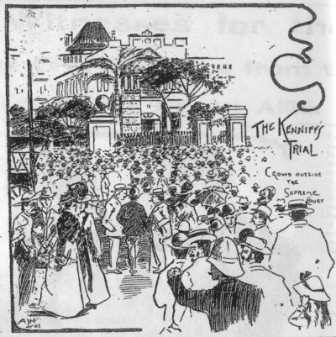

Images

from contemporary newspaper reports:

Left:

Crowds gathered outside

the Supreme Court building in George Street,

Brisbane, for the Kenniff trial;

Right:

The Kenniff family attending

the trial

sketches

from Sunday

Truth

newspaper, 9 November 1902;

20 July 1902 |

Conclusions

Despite all that I have said, it may safely be concluded that both Patrick and James Kenniff got what they deserved, according to the law and contemporary standards of punishment in 1902.

There remains no real doubt that Patrick Kenniff murdered both Albert Christian Dahlke and Constable George Doyle at Lethbridge's Pocket on 30 March 1902, and received the ultimate punishment which the law then mandated for such an offence.

James Kenniff may well have had some active participation in the death of Dahlke, or more likely Doyle. But, if so, his guilt was not proved beyond any reasonable doubt. On the charge of murder, he should have been acquitted.

By the same token, however, James Kenniff was plainly (at the very least) an accessory after the fact to wilful murder, and therefore liable to imprisonment with hard labour for life[56]. That, in fact, is the sentence to which his death sentence was commuted. Ultimately, he served 16 years in gaol for his part in the murders committed by his brother. Justice was done.

Justice was not, however, seen to be done. The trial of the Kenniffs, if not a travesty of justice, was certainly a miscarriage of justice - and a regrettable, and extremely rare, blemish on the otherwise distinguished judicial career of Sir Samuel Griffith. In summary, the features which made the trial gravely unsatisfactory are these:

(1) The fact that the trial was conducted before a "special jury": there was no proper basis for the prosecuting authorities to seek that mode of trial; it was plainly a tactical manoeuvre by the prosecuting authorities, to avoid the risk of a sympathetic jury comprised of men of a similar social standing to the Kenniffs; the approach taken by Justice Power in granting the application was legally erroneous; and the consequence was to deprive the Kenniffs of their fundamental right to a trial by a "jury of their peers".

(2) The defence case was not conducted competently: serious tactical errors were made in the conduct of the defence case; the Kenniffs should have been advised (if they were not advised) that they were sealing their own fates by calling alibi evidence which was plainly fabricated; the main arguments addressed on behalf of the Kenniffs were entirely implausible; and the strongest argument in favour of James Kenniff's innocence was not put to the jury, namely that there was no evidence on which the jury could find (let alone beyond any reasonable doubt) that James Kenniff was implicated in the murders of Doyle and Dahlke.

(3) The prosecution case was legally flawed: it was premised on the proposition that the murders occurred in the prosecution of a common intention formed by Patrick and James to prosecute an unlawful purpose in conjunction with one another, but there was simply no evidence from which the formation and existence of such a common intention could be inferred.

(4) The course of the trial was seriously irregular: the prosecution should have been required to elect at the commencement of proceedings, rather than at the conclusion of the prosecution case, whether to proceed on the charge regarding Doyle's death or that of Dahlke; and the fact that the prosecution was not required to make this election until the conclusion of the prosecution case had the propensity seriously to prejudice the Kenniffs' defence.

(5) The proceedings in the Full Court were also seriously flawed: having already expressed concluded views regarding the very issues reserved for the Full Court's consideration, Sir Samuel Griffith ought not to have participated in the Full Court proceedings; and his participation, in the circumstances, so infected those proceedings as to vitiate the outcome.

I think that the final words should go to Justice Real, whose courageous dissenting judgment in the Full Court, and whose heated exchanges with the Chief Justice during the course of argument, demonstrate a commendable passion for the belief that even the worst villains - and nobody doubts, for a moment, that the Kenniffs were villains of the worst order - deserve a fair trial. As his Honour said in the course of argument[57]:

"I do not see any real evidence that James Kenniff had anything to do with the murder; but I probably think he had. I think the chances are 50 to 1 - a thousand to one, if you like - that he had, but, as I said yesterday, it is the same principle on which you lynch people. ... I cannot see any evidence that he took part in the shooting. We have no right to draw the inference that because he could have done so he did. The probability is that he did, but the British law requires some proof."

|