|

On

just a few occasions in the history of the

Western World, fate or coincidence have

conspired to bring together, in the same

place and at the same time, a collection

of truly extraordinary individuals - individuals

whose collective impact on the political,

social and cultural development of mankind

has far exceeded the sum of their parts.

One such moment in history arose in Classical

Rome, under Julius Caesar, when the first

Emperor of the Known World rubbed shoulders

with Pompey the Great, Sulla, Cicero, Atticus,

Crassus, Brutus, Clodius, Catullus, and

Marcus Antonius. Likewise, in the Florence

of Lorenzo ("the Magnificent")

de Medici, a population of less than 100,000

included Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo,

Donatello, Botticelli and Machiavelli. So

it was that in Elizabethan London, a constellation

of historical stars came together in a city

less than one-tenth - perhaps as little

as one-twentieth - the size of modern-day

Brisbane.

It

seems more than accidental that this phenomenon

has often coincided with the regimes of

visionary autocratic rulers, and Elizabeth

I was no exception. This enigmatic woman's

45-year reign was, in many ways, the mid-point

between the absolute monarchy which preceded

the Great Charter of 1215, and the constitutional

monarchy presaged by the Bill of Rights

of 1689. The last of the Tudor sovereigns

was as autocratic as her father, Henry VIII,

but less vicious; no less cunning than her

cousin and successor, James I, but not so

duplicitous. The Virgin Queen's handling

of policy issues - domestic, foreign and

military - displayed a wisdom and subtlety,

strangely at odds with her petty and sometimes

childish behaviour amongst the members of

her court. She was naively prone to the

flattery of the handsome young men with

whom she surrounded herself, another trait

which she shared with James I. But,unlike

James, Elizabeth was masterful at playing

her retinue off against one another, and

possessed an uncanny ability to promote

her most loyal and talented retainers to

positions which suited their individual

skills.

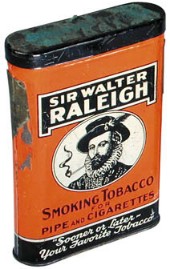

three popular views

of Sir Walter Raleigh: the chivalrous courtier;

the

explorer and colonist; the man who (supposedly)

introduced tobacco to Europe

Dominant

in her immediate circle was William Cecil,

Lord Burghley, often identified as the inspiration

for the character of Polonius in Shakespeare's

Hamlet - a "tedious old fool"

to the younger and more adventurous members

of the court, but a gifted administrator

who, as Secretary of State and later Lord

Treasurer, was largely responsible for the

financial and domestic security which characterised

the Queen's long reign. Burghley was in

due course succeeded as the Queen's principal

minister by his hunchbacked second son,

Sir Robert Cecil (subsequently 1st Earl

of Salisbury), whose political intrigues

were as crooked as his spine,and may have

contributed to the theatrical device often

employed by Shakespeare, of associating

physical deformities with deformities of

moral character. As a recent writer (Nieves

Mathews, Francis Bacon: The History of

a Character Assassination, 1996, p.236)

has observed: "A craving for political

power could be detected in the calculated

concentration with which Robert Cecil camouflaged

his wide network of corruption over the

years, so successfully that it has only

recently been uncovered."

Another

prominent figure at Elizabeth's court was

a shadowy character, Dr John Dee, who somehow

epitomises the collision of Dark Ages mysticism

and Renaissance learning. Dee would today

be described as the government's scientific

adviser, and he was undoubtedly a man of

great learning, especially in the fields

of mathematics, astronomy, geography and

navigation. But he also served as the Queen's

spiritualist and astrologer, conducting

séances and the like, and is said to have

inspired the character of Prospero in Shakespeare's

The Tempest. As a mariner, Sir Walter

Raleigh was naturally interested to obtain

the benefits of Dee's knowledge regarding

geography and navigation; but Dee's reputation

as a mystic and necromancer opened Raleigh

to the charge of being associated with atheism

and the "black arts".

|

Queen

Elizabeth I

|

Lord

Burghley

|

Raleigh,

himself, was something of an amateur scientist,

particularly interested in botanical specimens

obtained from the New World, and their potential

use for medicinal purposes; he is also remembered

(albeit inaccurately) as the person who

introduced the smoking of tobacco to Europe

- a dubious title which rightfully belongs

to his kinsman, the notorious privateer

Sir John Hawkins. In an age of religious

zealotry and heretical suspicion, Raleigh's

interest in genuine scientific experimentation

enhanced his reputation as dabbling in sorcery.

In

his heyday, he surrounded himself with some

of the most controversial intellects of

his age, including mathematicians, astronomers,

geographers and students of the natural

sciences, as well as poets, playwrights,

and philosophers. They met at Durham House,

the grand London residence which Queen Elizabeth

expropriated from the Bishop of Durham and

provided for Raleigh's use. This group is

often identified with the "School of

Night" in Shakespeare's Love's Labours

Lost.

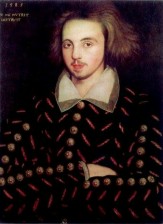

the

"School of Night" - Dr John Dee

and Christopher Marlowe

and Queen Elizabeth's

spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham

Elizabeth's

England enjoyed unprecedented advances in

military strength and strategic influence,

and in cultural development. The former

was achieved largely through the efforts

of privateers - in truth, little more than

licensed pirates - like Hawkins and Sir

Francis Drake, and more high-minded navigators

and explorers like Sir Humphrey Gilbert

and his half-brother, Raleigh. Elizabeth's

reign was also a golden age of literature,

though the brilliancy of the single greatest

writer in the history of the English language,William

Shakespeare, has tended to eclipse the lesser

lights of Christopher Marlowe, Edmund Spenser,

Ben Jonson, and John Lily.

There

is no record that Shakespeare and Raleigh

were personally acquainted, although they

had many mutual acquaintances. Shakespeare's

works contain a number of characters and

references arguably inspired by Raleigh

- including, as we shall see, an unambiguous

reference to Raleigh's trial. The character

of Armado in Love's Labours Lost

is thought to be a caricature of Sir Walter,

made all the more ironic because Raleigh's

fanatical hatred of the Spanish is parodied

by a character described as "a fanatical

Spaniard".

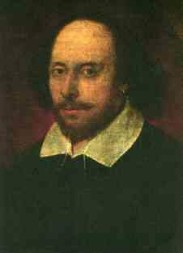

Raleigh's

literary circle: Edmund Spencer; Ben Johnson;

William Shakespeare

Raleigh's

literary connections included Ben Jonson

- sometime tutor to Raleigh's eldest son,

Wat - and the poet Edmund Spencer, to whom

Raleigh was a close friend and patron. A

rather more controversial connection existed

between Raleigh and Shakespeare's major

rival, Kit Marlowe, who was one of the Durham

House "School of Night". Marlowe

was a notorious atheist, and also

openly homosexual - to him is attributed

the aphorism, "All them who love

not tobacco and boys are fools."

When not writing plays, Marlowe was

on the payroll of Sir Francis Walsingham,

England's first semi-official spymaster.

In 1593, Marlowe was arrested and charged

before the Star Chamber with blasphemy and

treason; but was then (astonishingly) released

on bail. Within 10 days, he was dead - stabbed,

supposedly, in an argument over who should

pay the bill in a tavern at Deptford.

The credibility of this "official"

version of Marlowe's death is not enhanced

by the fact that Marlowe actually died at

a private home - owned, coincidentally,

by a cousin of Cecil's - rather than a tavern;

the fact that the man who inflicted the

fatal wound, along with his two companions,

were all members of Walsingham's secret

service; and the fact that the killer

rapidly received a royal pardon, and immediately returned

to Walsingham's service. The true circumstances

surrounding Marlowe's death have been

debated ever since, with conspiracy

theories ranging from the possibility that

Marlowe was a double-agent who had

to be eliminated to protect state secrets;

that his death was necessary to prevent

his implicating others when he came to trial

before the Star Chamber; that he was the

victim of a power play between the competing

Cecil, Walsingham, Essex and Raleigh factions

at court; that his death was "staged",

and that he in fact survived with a new

identity provided by his secret service

employers, possibly to avoid his impending

Star Chamber trial (and then went on,

as it has been suggested, to "ghost

write" Hamlet and other plays

usually attributed to Shakespeare); or that

his homosexual liaison with a prominent

courtier was a potential source of

embarrassment. Raleigh has from time

to time been implicated in each of these

conspiracy theories, except the last - not

even the most fanciful of them has

ever challenged Raleigh's sexual orientation.

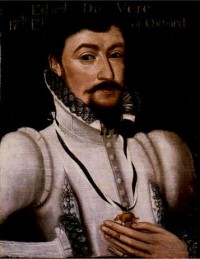

The

writing of poetry (though not plays)

was regarded as a significant gentlemanly

attainment amongst the inner circle

at Elizabeth's court, and the noted

poets of the age included three of

Her Majesty's gentleman-soldiers, Sir Philip

Sidney, Edward De Vere (17th Earl

of Oxford) and Raleigh. The predominance

of aristocratic literati at

Elizabeth's court has led to the suggestion

- mainly emanating from the "lunatic

fringe" of serious literary study

- that William Shakespeare was in fact the

nom de guerre of a high-born author

who preferred to conceal his true identity,

or perhaps the barely literate "front

man" for the supposed "real"

author: maybe the Earl of Oxford, maybe

Sir Francis Bacon, maybe Christopher Marlowe,

maybe the Earl of Derby, maybe Raleigh (with

or without collaboration from Bacon), or

maybe even the Queen herself.

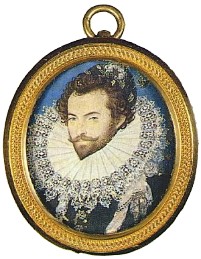

Gentleman-poets

of Elizabeth's Court: Sir Philip

Sidney, the Earl

of Oxford, and Raleigh

Elizabeth's

reign also produced a number of outstanding

jurists. But in the legal world, as

in the literary world, the fame of

one has tended to out-shine the many;

and that one was Sir Edward Coke. Amongst

his contemporary lawyers, Ellesmere

and Bacon are perhaps better remembered for

their feuds with Coke, and in Bacon's case,

for his philosophical and other non-judicial

writings.

|