|

Raleigh's name was first mentioned by

Brooke, when he accused Cobham. Brooke offered

no evidence against Raleigh directly, but

named him as a person whom the conspirators

in the Main Plot regarded as a "fit

man" to join with them. This meant

nothing in itself: even under the oppressive

treason laws of the day, a man could not

be convicted merely because others mooted

him as one who might be approached to join

a conspiracy. And anyone seriously contemplating

an armed insurrection would have been stupid

not to consider Raleigh's name, given his

(by this time) well-known fall from grace

under the new King, his vast military and

administrative experience, and his significant

connections with people of influence. But

even the fact that Brooke had mentioned

Raleigh's name was sufficient ground to

interrogate him.

At their initial interrogations, both

Raleigh and Cobham denied any knowledge

of the Main Plot. A few days later, a merchant

from Antwerp, Matthew la Renzi (or Laurency)

came forward, and admitted carrying correspondence

between Aremberg and Cobham. He also deposed

to a secret meeting between Aremberg and

Cobham. More significant, so far as Raleigh

was concerned, was the claim that Raleigh

was present when a letter from Aremberg

was delivered, and that Cobham and Raleigh

had gone "into a chamber privately"

to read the correspondence.

Raleigh was again interviewed, and again

denied any knowledge. But, in an apparently

genuine attempt to assist the investigation,

he sent a letter to the Privy Council, stating:

"If your honours apprehend the

merchant of St Helen's, the stranger

will know that all is discovered of

him, which perchance you desire to conceal

for some time. All the danger will be

lest the merchant fly away. If any man

knows more of the Lord Cobham, I think

he trusted George Wyet [Wyatt] of Kent."

There can be little question about Raleigh's

sincerity in writing this letter. The "merchant

of St Helen's" was obviously la Renzi;

"the stranger" was obviously Aremberg;

Raleigh was making the helpful suggestion

that la Renzi should not be arrested, lest

it serve as a "tip off" to Aremberg

and other conspirators. He was also suggesting

that useful information about Cobham could

be obtained from Wyatt.

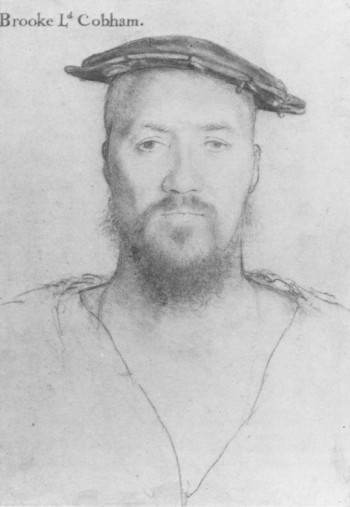

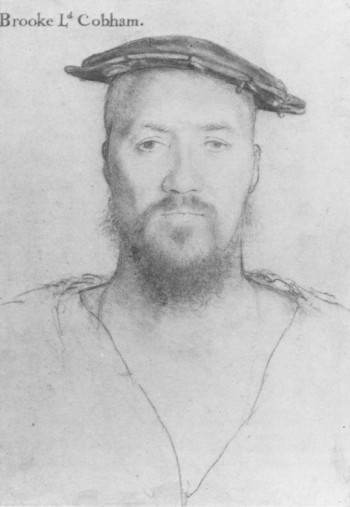

Lord

Cobham

Cobham was shown this letter during a

subsequent interrogation, and immediately

"broke out into passion", believing

that Raleigh was determined to implicate

him. Cobham cried out: "Oh villain!

Oh traitor! I will now tell you all the

truth", and then admitted to the negotiations

with Aremberg, but claimed that it was all

Raleigh's idea, and that he (Cobham) would

not have become involved but for Raleigh's

influence.

Raleigh was arrested, and imprisoned

in the Bloody Tower pending trial. Normally,

and for obvious reasons, treason trials

were held very swiftly. But Raleigh's imprisonment

continued from the end of July until early

November. Possibly this was due, in part,

to an outbreak of plague in London; but

more likely, the Privy Council knew how

weak was the case against Raleigh - based

on the testimony of a single witness, and

him a co-conspirator - and determined to

wait in the hope that further evidence would

turn up.

Far from producing further evidence to

implicate Raleigh, the delay weakened the

case against him, as Cobham recanted of

his allegations. Then, at a further interview,

Cobham repeated the allegations, claiming

that he had retracted them only because

of his fear of Raleigh.

This was itself a bizarre claim, given

that both Cobham and Raleigh were imprisoned,

and facing trial for their lives. What greater

risk could Raleigh pose to Cobham, than

the risk which his own confession had called

upon himself: the risk of the gruesome punishment

then meted out to convicted traitors, of

being drawn on a hurdle through the streets

of the capital, hanged, disembowelled, castrated,

decapitated, then to have one's body hacked

into quarters, with the four parts being

displayed on the gates to the City, and

the head left to rot on a staff over London

Bridge - added to which was the penalty

of attainder or "corruption of the

blood", by which all of the convicted

traitor's worldly goods were forfeited to

the Crown, and the traitor's family were

denied any inheritance from or through the

traitor? And even if it could be supposed

that Raleigh was in a position to do Cobham

any greater harm than that, Cobham's best

protection was to have Raleigh kept in secure

confinement.

The suggestion that Cobham withdrew his

allegations against Raleigh out of fear

does not bear scrutiny. If anyone was in

a position, either to terrify or to reward

Cobham, it was the Privy Council - Cecil,

in particular. Though Cobham had no hope

of escaping conviction as a traitor, it

was unusual for a member of the nobility

to suffer the full rigours of the punishment

prescribed by law, and Cobham could at least

hope merely to be beheaded. But, were he

to make himself useful to the King (and

Cecil), there was even some chance of his

sentence being commuted to one of imprisonment

- and of his family continuing to enjoy

his hereditary title and property. The suspicion

that a deal was done with Cobham is strengthened

by the fact that, following his and Raleigh's

convictions, Cobham immediately received

a full pardon.

In the lead-up to Raleigh's trial, Cobham

again sought to withdraw his allegations

against Raleigh, writing to the Governor

of the Tower to arrange an interview with

the Privy Council, saying: "God is

my witness, it doth touch my conscience

… . I would fain have [back] the words that

the Lords used of my barbarousness in accusing

him falsely". But the Governor withheld

the letter until after Raleigh's conviction.

Due to the continuing plague in London,

the trial was held in the Great Hall of

Winchester Castle - to this day, apart from

the great Gothic Cathedral, Winchester's

main tourist attraction, where credulous

Americans are shown King Arthur's Round

Table, and the equally apocryphal nook from

which James I is said to have eavesdropped

on Raleigh's trial (James was in fact nowhere

near Winchester at the time).

On a charge of treason, the prisoner

was committed to trial by the Privy Council

- not its Judicial Committee, which evolved

in later years, but the council of the King's

Ministers of State - so there were no committal

proceedings in the modern sense.

Raleigh had never been a popular figure,

and the mere accusation of treason was sufficient

to turn the mob against him. Raleigh was

despatched from the Tower to Winchester,

in his own coach, with an escort of 50 horsemen,

led by Sir William Waad and Sir Robert Mansell.

He was pelted with sticks, stones and mud

- and with tobacco pipes - and Waad wrote

that it was "hob or nob" whether

Raleigh "should have been brought out

alive through such multitudes of unruly

people as did exclaim at him". The

75 mile trip took five days, leaving Raleigh

less than 48 hours to prepare for his trial

on 17 November 1603.

Thus Raleigh came to trial for his life,

on the accusation of a single witness, a

confessed co-conspirator, who had everything

to gain and nothing to lose from implicating

Raleigh, and who had twice retracted his

accusations against Raleigh.

|