|

The

law of treason at the time of Raleigh's

trial was largely unchanged since 1352,

when a statute of Edward III defined treason

to include "compassing or imagining"

the monarch's death. Essentially the same

provisions were enacted in Queensland, as

part of Sir Samuel Griffith's Criminal

Code in 1899 (s.37), and were only repealed

in 1997. Similar provisions appeared in

the Commonwealth Crimes Act 1914,

section 24, and now section 80.1 of the

Criminal Code Act 1995. The death

penalty has, of course, been abolished in

Australia; and also - very recently - in

the United Kingdom.

At

the time of Raleigh's trial, the manifestation

of an "overt act" was apparently

necessary where the treason alleged was

"adhering to the King's enemies",

but not in the case of a treason by way

of "compassing or imagining" the

King's death. But even so loose a concept

as "compassing or imagining" the

King's death was made more nebulous by the

proposition that any plan of action likely

to imperil the King's life was sufficient,

though the King's death was neither intended

nor contemplated. So it was laid down in

Sir Matthew Hale's Pleas of the Crown

that a conspiracy to imprison the King by

force, or the assembling of a company with

that object, sufficed - on the reasoning,

as supposed by Blackstone (4 Bl.Com. 79),

of the "old observation, that there

is generally but a short interval between

the prisons and the graves of princes"

[spelling modernised].

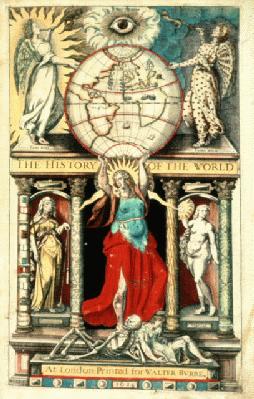

title-page

to The History of the World,

written

by Raleigh whilst a prisoner in the Tower

of London.

when originally published,

Raleigh’s name did not appear in the book;

being

attainted for treason, Raleigh was “legally

dead”.

Even

if Raleigh had known the full extent of

the Main Plot, as devised by Brooke and

Grey, it did not involve the death of King

James; merely his replacement, as sovereign,

by Lady Arabella Stuart. And Raleigh's alleged

role, put at its highest, was merely to

assist in the distribution of funds to support

an undertaking of which he did not know

the details. At his trial, Raleigh was taunted

by Coke with a statement that Watson and

Markham, both involved in the Bye Plot,

had heard Brooke attribute to Cobham, in

the words: "There is no way of redress

save only one, and that is to take away

the King and his cubs, not leaving one alive".

This was, at best, third-hand hearsay; and

even then, it did not in any way implicate

Raleigh. But it was adduced against Raleigh,

apparently, as evidence that the course

of action which Raleigh "compassed

or imagined" placed the King in mortal

danger.

Thus

Raleigh was prosecuted on the footing that

he possessed a certain state of mind, though

there was no requirement that his state

of mind be communicated to anyone else,

or that it be put into action; and in fact,

no evidence, even from Cobham, that Raleigh

was privy to any proposal which imperilled

the King's safety. Yet the alleged traitor

was considered incompetent to give evidence

on his own behalf, in defence of the allegation

that he possessed a felonious state of mind.

As

Blackstone notes (4 Bl.Com. 352):

"

… it was an ancient and commonly received

practice … that, as counsel was not

allowed to any prisoner accused of a

capital crime, so neither should he

be suffered to exculpate himself by

the testimony of any witnesses."

[spelling modernised]

But

Blackstone also adds (ibid., p.357):

"Sir

Edward Coke protests very strongly against

this tyrannical practice: declaring

that he never read in any act of parliament,

book-case, or record, that in criminal

cases the party accused should not have

witnesses sworn for him; and therefore

there was not so much as scintilla

juris against it." [spelling

modernised]

Coke's

protest was not, of course, heard when he

appeared to prosecute Raleigh; so Raleigh

had to defend himself, without legal representation,

neither permitted to give evidence on his

own behalf, nor to call witnesses in his

defence.

But

on a charge of high treason, in Raleigh's

time, the defendant laboured under a further

and even more extreme disadvantage: prosecution

witnesses were not called to give oral testimony,

or made available for cross-examination;

the prosecution merely read their depositions

- and indeed, only those parts of the depositions

which supported the prosecution case.

This

was critical in Raleigh's trial, because

Raleigh had every reason to suppose that

Cobham might again recant if giving testimony

viva voce. Though there is no complete

transcript of the proceedings, Raleigh's

submissions can be pieced together from

a number of sources; what he said was to

this effect -

"I

claim to have my accuser brought here

face to face to speak. The Proof of

the Common Law is by witnesses and jury:

let Cobham be here, let him speak it.

If you proceed to condemn me by bare

inferences, without an oath, without

subscription, upon a paper accusation,

you try me by the Spanish Inquisition.

If my accuser were dead or abroad, it

were something, but he liveth, and is

in this very house. Consider, my Lords,

it is not a rare case for a man to be

falsely accused; aye, and falsely condemned

too. I beseech you, my Lords, let Cobham

be sent for, charge him on his soul,

on his allegiance to the King: let my

Accuser come face to face, and be deposed.

If Cobham will maintain his accusation

to my face, I will confess myself guilty."

Cobham

was not produced, Chief Justice Popham offering

the explanation that "there must not

such a gap be opened for the destruction

of the King as would be if we should grant

the application". In other words, where

a man is on trial for his life for an alleged

treason, a "gap [would] be opened for

the destruction of the King" if the

person accused were given a fair opportunity

to test, by the process adopted in every

other branch of the law - namely, by cross-examination

of adverse witnesses - the veracity of the

accusation.

Chief

Justice Sir John ("Pompous") Popham

The

circularity of this process of reasoning

is self-evident: it only begins to make

any kind of sense if one starts with the

presumption that the person accused is guilty,

so that any weakness in the prosecution

case demonstrated by effective cross-examination

involves the risk that a traitor may escape

punishment. Whilst (as Raleigh pointed out)

for all other purposes the Common Law regards

the production and cross-examination of

witnesses as an indispensable component

in ascertaining the truth, that ingredient

was omitted only in the class of cases where,

one might think, ascertainment of the truth

was of the utmost importance. Plainly, it

is of no little importance to the man whose

life is (quite literally) at stake; but

even if "the destruction of the King"

were - as "Pompous Popham" suggested

- a relevant consideration, surely the greatest

protection for the King was to establish

the truth, rather than convicting an innocent

and loyal subject, and taking the risk that

the real traitors may escape unpunished.

Raleigh's

trial ultimately produced some beneficial

effects. Mention has already been made of

Coke's attitude (as subsequently expressed)

to the practice which denied the accused

the right to give evidence, or to call evidence

in his behalf; and, before the Century was

out, those rights were expressly conferred

on defendants in all cases by Act of Parliament.

So, too, the right to legal representation

was eventually extended to the accused in

all criminal cases. By Blackstone's time,

it was also well settled that, in any case

of high treason, the prosecution must produce

at least two witnesses, either testifying

to the same overt act of treason, or to

two separate overt acts of the same nature

of treason.

Raleigh's

trial holds a special place in the jurisprudence

of the United States of America, where the

Sixth Amendment to the Constitution specifically

requires, in all criminal prosecutions,

that the accused "be confronted with

the witnesses against him". In California

v. Green, (1970) 399 U.S. 149 at 146,

the US Supreme Court noted:

"A

famous example is provided by the trial

of Sir Walter Raleigh for treason in

1603. A crucial element of the evidence

against him consisted of the statements

of one Cobham, implicating Raleigh in

a plot to seize the throne. Raleigh

had since received a written retraction

from Cobham, and believed that Cobham

would now testify in his favour. After

a lengthy dispute over Raleigh's right

to have Cobham called as a witness,

Cobham was not called, and Raleigh was

convicted. … At least one author traces

the Confrontation Clause [in the Sixth

Amendment to the US Constitution] to

the common-law reaction against these

abuses of the Raleigh trial."

|