|

Elizabeth

died in 1603, without having named her successor.

Cecil was present at her death-bed, and

we only have his word for it that, when

he enquired of the dying Queen whether James

should succeed her, she made a motion indicating

her assent. Cecil lost no time in ensuring

that his long efforts to ingratiate himself

with James would bear fruit. He immediately

issued orders for the accession of James

to be publicly proclaimed throughout the

Kingdom, and sent a despatch-rider to Scotland

to summon the new King, then himself set

out to meet James on his progress to London.

In

due course, Cecil was to become the power

behind James's throne, just as his father,

Burghley, had been the power behind Elizabeth's.

Aside from Cecil, James's principal courtiers

were characterised by two qualities - their

outstanding good looks, combined with an

almost total ineptitude in matters of public

administration. His first favourite, Sir

Robert Carr - later Earl of Somerset - was

rewarded with the gift of Raleigh's country

house, Sherborne, following the forfeiture

of Raleigh's worldly possessions upon his

being attainted for treason. After Carr

fell from grace, he was displaced by Sir

George Villiers - later Earl, then Marquis,

and finally Duke of Buckingham. The King

was not alone in his susceptibility to the

attractions of Buckingham's physical beauty:

Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, recorded

"a delightful dream in which Villiers

came into his bed";and even Bacon wrote,

in response toa letter from Villiers, that

"the flame it hath kindled in me will

never be extinguished". King James

wrote to Buckingham, whom he nicknamed "Steenie",

as "my only sweet and dear child",

as "sweetheart", and even as "wife".

|

|

|

|

the

King and his "toy-boys"

(above)

Jame I

(upper right)

Robert Carr

(lower right)

George Villiers

|

With

Essex out of the way, and with the King's

"toy boys" providing no real threat

to Cecil's control of the government, only

Raleigh could be seen as a serious challenge

to his power and influence under the new

regime. But, quite apart from Raleigh's

own (honourable but foolish) refusal to

accept friendly overtures from Lennox on

James's behalf, Cecil had well and truly

poisoned the well between James and Raleigh.

In secret correspondence with James in the

last years of Elizabeth's life, Cecil had

insinuated that Raleigh was opposed to James's

succession, preferring one of the female

claimants - either Lady Arabella Stuart,

who had a more direct lineal claim, or possibly

the Spanish Infanta - whom Raleigh might

be able to manipulate as successfully as

he had manipulated Elizabeth. Similar insinuations

had been communicated to James by Essex

- who also implicated Cecil as favouring

the Infanta - and by Lord Admiral Howard

(later the Earl of Nottingham). Thus, when

James and Raleigh first met, James was already

thoroughly prejudiced against Raleigh, making

the famous pun: "Raleigh, Raleigh,

O my soul, mon, I have heard but rawly of

thee".

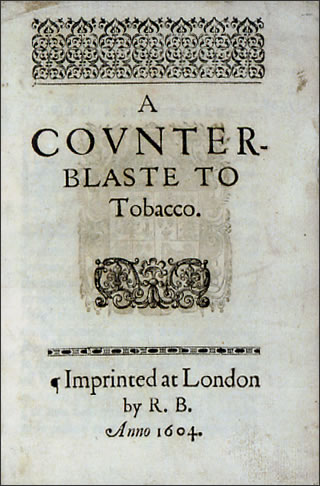

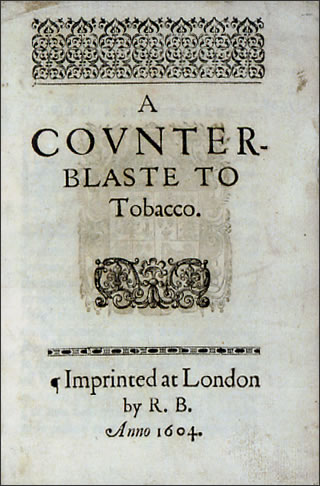

Perhaps

there is another reason for James's animosity

to Raleigh, namely Raleigh's reputation

for having introduced the smoking of tobacco

to England. In an essay published in 1604,

entitled A Counterblaste to Tobacco,

James issued what was probably the first

"Government Health Warning" on

this subject, describing smoking as "a

custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to

the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous

to the lungs, and in the black stinking

fume thereof nearest resembling the horrible

stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless".

In what was quite possibly a reference to

Raleigh, James's essay mentioned "the

foolish and groundless first entry thereof

into this Kingdom", observing that

"It was neither brought in by king,

great conqueror, nor learned doctor of physic".

Title-page

to A Counterblaste to Tobacco

But

Raleigh was a political survivor. He had

reversed Elizabeth's disfavour more than

once, and outlasted all of her principal

courtiers apart from Cecil. Realistically,

there was little chance that Raleigh would

ever overcome the new King's animosity to

him; but that risk was not one which Cecil

was prepared to take.

Possibly,

Cecil had another reason for wanting Raleigh

out of the way. His own role in bringing

down Essex was not calculated to endear

him to the new King, and James - a homosexual

or bisexual with a particular attraction

to dashing young men of good looks and heroic

attainments - formed a strong posthumous

attachment to his "martyr". At

his trial, Essex had attempted to deflect

attention from his own treason by declaring

that he could "prove thus much from

Sir Robert Cecil's own mouth: That he, speaking

to one of his fellow councillors, should

say that none in the world but the Infanta

of Spain had the right to the Crown of England."

There can be little doubt that Cecil did,

indeed, "hedge his bets". Throughout

his time in government service, and even

whilst England was at war with Spain, Cecil

was in receipt of a Spanish "pension"

- that is, regular bribes from the Spanish

Crown. If there were any truth in Essex's

allegation that Cecil and Raleigh supported

the Infanta's claim to the succession, Raleigh

was the only man alive who could betray

Cecil. Cecil needed Raleigh eliminated.

|