|

Raleigh's

imprisonment was not quite so severe as

might be imagined; he was allowed servants,

and given every facility to pursue his interests

as a writer and as an amateur student of

science. For some time, his wife and family

were permitted to reside with him in the

Tower, and he was allowed regular visitors.

He became a hero to King James's eldest

son, Prince Henry, the Prince of Wales,

who petitioned his father for Raleigh's

release, and famously remarked: "Sure

no king but my father would keep such a

bird in a cage". But Henry's untimely

death, in 1612, deprived Raleigh of any

further support from that quarter.

Finally,

in 1616, at the age of 64, and having suffered

two strokes whilst in the Tower, Raleigh

was released to lead a further expedition

to Guiana, in search of El Dorado. The venture

was a complete failure, and led to the death

- amongst many others - of Raleigh's eldest

son, Wat. Unfortunately for Raleigh, a detachment

sent by him into Guiana encountered a Spanish

settlement; there was fighting and bloodshed,

and a number of the Spanish were killed.

When Raleigh returned to England, without

the gold with which James had hoped to enrich

his treasury, James was more than willing

to accommodate demands for Raleigh's execution

by the Spanish Ambassador, the Conde de

Gondomar. But James was afraid that the

good account which Raleigh made of himself,

at the treason trial, would be repeated

- to Raleigh's benefit, and James's detriment

- so James sought a way to rid himself of

Raleigh without a further trial.

At

this point, reference should be made to

another famous figure in the history of

English law, Francis Bacon - by then, Lord

Chancellor and Baron Verulam, subsequently

to become Viscount St Albans. Whatever fame

and respect Bacon is entitled to as an essayist,

philosopher and scientist, he is surely

one of the most odious creatures ever to

have disgraced judicial office at any time

or in any place. We have already seen how

he turned against his former patron, the

Earl of Essex, when Essex was on trial for

his life. At Elizabeth's request, and for

a substantial fee, he wrote a vicious account

of that trial; but, no sooner had James

ascended the throne, than Bacon again put

pen to paper, by way of an apologia

for James's "martyr". We have

seen, too, how he destroyed the judicial

career of the learned and sagacious Coke,

of whose brilliance and success Bacon was

profoundly jealous.

The

career of this undoubtedly talented lawyer

and scholar reached a fitting culmination

when he was impeached for accepting bribes

- an almost unique instance of graft in

the long and glorious history of the English

judiciary. Bacon's apologists, who are numerous,

argue that the acceptance of bribes by judges

was a common thing in Bacon's time, and

that Bacon did not allow the bribes to influence

his decisions. However, when James I (with

Bacon's assistance) was looking for an excuse

to sack Coke, Coke's conduct as Chief Justice

was subjected to the most meticulous examination,

and no plausible instance of any form of

corruption could be discovered. Nor does

it seem very probable that the bribes which

Bacon accepted were without any influence

on the exercise of his judicial powers;

yet, even if that were the case, it is difficult

to see how his conduct in accepting bribes

is made more virtuous by the fact that he

cheated the people who bribed him, by not

giving them the benefit of the influence

for which they had paid.

Bacon

was amongst the many visitors received by

Raleigh in the Tower, and it seems that

they became firm friends. Most likely, Bacon

had a very genuine interest in Raleigh's

scientific study and Raleigh's writings;

it may be the case that they collaborated

on some works, which for political reasons

Bacon could not risk publishing under his

own name; and they have even been linked,

in one of the more far-fetched emanations

of the Shakespeare "authorship controversy",

as jointly the "real" authors.

It was therefore natural that, when Raleigh

was offered his freedom to undertake the

expedition to Guiana, he sought Bacon's

advice. Raleigh was provided with a Commission

from the King, which not only gave Raleigh

liberty to undertake the voyage, but vice-regal

powers over the entire expedition, including

the power to dispense justice. Raleigh reportedly

asked Bacon whether he should seek the insertion

of a provision, formally pardoning him of

his previous treason conviction. Bacon's

advice to Raleigh was that a formal pardon

was unnecessary: that Raleigh had "a

sufficient pardon for all that is past already,

the King under his Great Seal having made

you Admiral, and given you power of marshal

law".

|

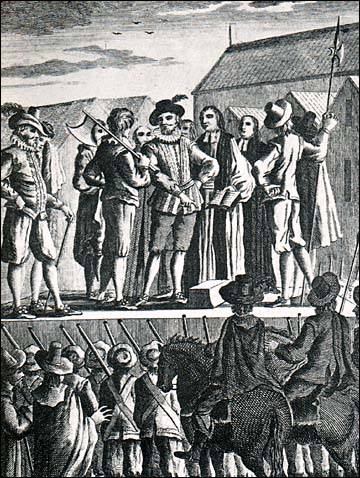

Raleigh

(in old age)

|

Bacon

|

However,

after Raleigh's return from Guiana, and

when James sought the Privy Council's advice

as to how Raleigh should be dealt with,

it seems that Bacon was the first to suggest

that the King could obtain execution of

the sentence passed 15 years earlier. Other

members of the Privy Council scrupled at

the injustice of beheading Raleigh after

so long; some even argued that, whatever

the legalities of the situation, it was

distinctly dishonourable to treat Raleigh

as being still attainted of treason, after

he had been commissioned to undertake a

difficult and dangerous voyage of exploration

for the Crown's benefit, and had lost his

son in the process. The Privy Council provided

James with a number of options: a new trial

with new charges; a commission of inquiry

regarding the failed Guiana expedition,

with the possibility of a recommendation

that Raleigh's previous sentence be carried

into effect; or an application to the Court

of King's Bench for execution of the previous

sentence. But James, determined not to allow

Raleigh any further opportunity to increase

his popularity, would not contemplate any

possibility which allowed Raleigh again

to reclaim the public sympathy which he

had won over at Winchester, 15 years earlier.

So,

on 28 October 1618, a Writ of Habeas

Corpus was delivered to the Lieutenant

of the Tower, commanding that he bring Raleigh

before the King's Bench at Westminster.

The attorney-general, Henry Yelverton, applied

for "Execution of the former Judgment".

In Cobbett's State Trials, it appears

that Coke presided; but this cannot be correct,

as Coke had been dismissed as Chief Justice

two years earlier; in fact, Sir Henry Montague

presided as Chief Justice. Unlike the previous

proceedings, Raleigh was addressed with

particular courtesy and civility:

"I

am here called to grant Execution upon

the Judgment given you fifteen years

since; for which time you have been

as a dead man in the law, and might

at any minute have been cut off, but

the king in mercy spared you. … I know

you have been valiant and wise, and

I doubt not but you retain both these

virtues, for now you shall have occasion

to use them. Your faith hath heretofore

been questioned, but I am resolved you

are a good Christian; for your Book,

which is an admirable work, doth testify

as much. I would give you counsel, but

I know you can apply unto yourself far

better than I am able to give you; yet

will I, with the good neighbour in the

Gospel, who finding one in the way,

wounded and distressed, poured oil into

his wounds, and refreshed him, I give

unto you the oil of comfort; though,

in respect that I am a minister of law,

mixed with vinegar. Sorrow will not

avail you in some kind: for, were you

pained, sorrow would not ease you; were

you afflicted, sorrow would not relieve

you; were you tormented, sorrow could

not content you; and yet, the sorrow

for your sins would be an everlasting

comfort to you. You must do as that

valiant captain did, who perceiving

himself in danger, said, in defiance

of death; 'Death, though expectest me,

but manage thy spite, I expect thee'.

Fear not death too much, nor fear not

death too little: not too much, lest

you fail in your hopes; not too little,

lest you die presumptuously. And here

I must conclude with my prayers to God

for it; and that He would have mercy

on your soul. Execution is granted."

Thus,

having 15 years before been convicted of

treason on the pretext of a traitorous conspiracy

with the Spanish, he was now condemned to

die at the behest, ultimately, of the Spanish

Ambassador. As was remarked by his only

surviving son, Carew, Sir Walter "was

condemned for being a friend to the Spaniard;

and lost his life for being their enemy".

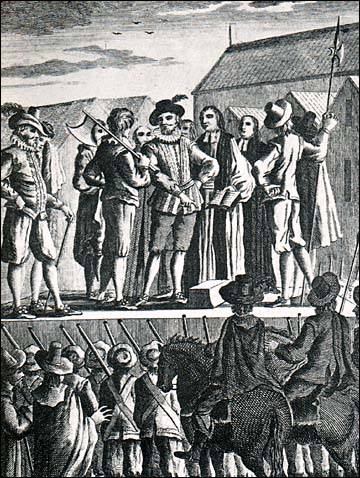

Raleigh's

execution

Raleigh

met his death on the scaffold, at Old Palace

Yard, Westminster, the following morning.

On the scaffold, he showed remarkable courage

and placidity. Inspecting the headsman's

axe, he remarked: "This is sharp medicine,

but it is a physician for all diseases".

He declined a blindfold, but - according

to legend - was permitted to smoke his pipe;

supposedly the first example of the traditional

indulgence for a condemned man. He made

a moving and dignified speech to the assembled

crowd and, before placing his head on the

block, proceeded to each corner of the scaffold

kneeling and asking the onlookers to pray

for him. When finally Raleigh placed his

head on the block, somebody suggested that

he was facing the wrong direction - that

he should face "the east of our Lord's

arising" - Raleigh replied that: "So

the heart be right, it is no great matter

which way the head lieth". But, to

oblige the crowd, he stood up and rearranged

himself. When he made the signal that he

was ready, the axeman hesitated, so Raleigh's

last words were: "Strike man, strike!".

Yet

subsequently, in Raleigh's cell, was found

a poem, apparently written by during his

last night:

Even

such is time, that takes in trust

Our

youth, our joys, our all we have,

And

pays us but with earth and dust;

Who,

in the dark and silent grave,

When

we have wandered all our ways,

Shuts

up the story of our days;

But from

this earth, this grave, this dust,

My

God shall raise me up, I trust.

|